Brendan Thornton lures students into his class with zombies, vampires and demons, then hits them with the serious stuff.

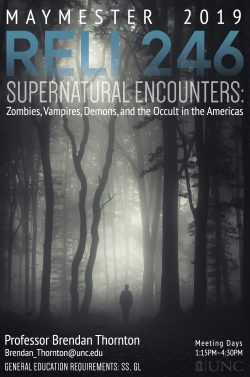

“My Flintstone vitamin class.” That’s how Brendan Thornton describes his Maymester course, Supernatural Encounters: Zombies, Vampires, Demons and the Occult in the Americas.

“Students will take it because it’s fruity and like a cartoon character, but there are vitamins there,” said Thornton, a cultural anthropologist and associate professor of religious studies.

Think zombies can’t really spark serious discussion? Sit in on Thornton’s Zoom classroom and listen to students debate what the shopping mall setting of “Dawn of the Dead” says about America’s consumer-oriented culture or discuss race and gender roles in fighting zombies in “Night of the Living Dead.” (Read this Discover story for the student perspective on the course.)

Thornton first brought together supernatural elements from his other religion courses for a seminar in 2015, and it quickly became his most popular lecture class, drawing 60 to 180 students each time. It’s also the only one of his classes that he teaches during Maymester. This summer was his first time teaching it online.

Despite its catchy name, the course has a syllabus that warns about homework — especially in the condensed three weeks of Maymester: “There is a lot of reading for this class. If you are not going to do the reading — DO NOT TAKE THIS CLASS!”

Thornton thinks of the class as “the anthropology of the supernatural,” emphasizing the way students learn how to understand religion from a social science — not a theological — perspective.

“One of the most common questions that I get from students is, ‘Is this real? Is this true?’ But that’s the wrong question,” he said. Whether zombies, vampires and other monsters exist is not the point. “It’s about what is being communicated by these stories.

For example, the course covers the pishtacos of the highland Andes — tall, hairy white men who come into town, murder natives, steal their fat and become rich. With the history of white European exploitation of South America and its native peoples, the origins of the story are fairly obvious. But fear of the pishtaco is so embedded in some Andean cultures that the natives still don’t trust foreigners.

“These stories really function as a warning to not trust foreigners and outsiders, particularly whites and mestizos. And the stories are real in their consequences. Any foreigner can be accused of being a pishtaco,” he said. A U.S. Food for Peace program to provide meals to Peruvian schoolchildren during a famine in the 1960s was seen by some as a clever pishtaco ploy.

“The response in one community was to stop sending kids to school,” Thornton said. “They said, ‘You’re clearly just fattening up our children so that you can steal their fat.’”

Zombie origins

Unlike the Andian pishtaco, the zombie that originated in Haitian folklore is not the real monster. “The folklore of the Haitian zombie is a story about being turned into a zombie and being forced to labor even after death,” said Thornton. “The fear is actually of the sorcerer who turns you into a zombie and makes you a slave.”

The first zombie movie, 1932’s “White Zombie,” keeps the Haitian story intact, showing undead enslaved Haitians continuing to toil on a sugar plantation. Before watching the movie, students read scholarly journal articles on how the movie illustrates the colonial power’s fear of becoming enslaved by the native Haitians.

The first zombie movie, 1932’s “White Zombie,” keeps the Haitian story intact, showing undead enslaved Haitians continuing to toil on a sugar plantation. Before watching the movie, students read scholarly journal articles on how the movie illustrates the colonial power’s fear of becoming enslaved by the native Haitians.

And while the class discusses that theory, they also look at the movie in the context of its Hollywood era, including the poster with the lurid tagline: “With these zombie eyes he rendered her powerless! With this zombie grip, he made her perform his every desire!”

So it turns out that the sugar plantation zombies are only a backdrop for what is really an ethno-erotic thriller, starring actor Bela Lugosi, fresh from his star turn as “Dracula,” as another exotic master manipulator of the virginal heroine.

In 1968’s “Night of the Living Dead,” the zombie myth takes another twist. Instead of being controlled by a sorcerer who wants to use them as slaves, these zombies may have been reactivated by some alien force. They don’t work; their only purpose seems to be consumption as they attack living people and either eat them or turn them into zombies, too.

Director George Romero focuses less on the zombies than on how ordinary people react to this new crisis — who wants to hide, who wants to fight, who has a plan. “For him, the movie is about the collapse of the traditional family and the possibility of revolution,” Thornton said.

Conspiracy theories

“What I do hope is that they will take three or four concepts with them that will lead them to think about and see the world they live in very differently,” Thornton said.In daily three-hour classes over three weeks, the students explored supernatural stories throughout the Americas, learning to look beyond the monsters to find their meaning.

Meanwhile, the associate professor is preparing for a class he’s introducing this fall. The new course is about conspiracy theories.

“Conspiracy theories are modern U.S. upper-middle-class light folklore. They’re always based on a little bit of truth, on something that’s secret. And we assume the secret is really powerful. That’s why we assume that Freemasons aren’t just sitting around playing cards and drinking beer. They’re ruling the world,” he said.

And while he didn’t bring up the pandemic in his class on the supernatural because he was “burned out on the topic,” Thornton will definitely cover it in this fall’s class.

“I’m sure there will be a lot more conspiracy theories out there to discuss,” he said.

By Susan Hudson, The Well