A team of researchers, led by astrophysicist Sumner Starrfield of Arizona State University, has combined theory with both observations and laboratory studies and determined that a class of stellar explosions, called classical novae, are responsible for most of the lithium in our galaxy and solar system.

The results of their study have been recently published in the Astrophysical Journal of the American Astronomical Society.

“Given the importance of lithium to common uses like heat-resistant glass and ceramics, lithium batteries and lithium-ion batteries, and mood altering chemicals; it is nice to know where this element comes from,” said Starrfield, who is a Regents Professor with ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and a Fellow of the American Astronomical Society. “And improving our understanding of the sources of the elements out of which our bodies and the solar system are made is important.”

Nuclear astrophysicist Christian Iliadis, who is the J. Ross Macdonald Distinguished Professor in UNC-Chapel Hill’s College of Arts & Sciences, was a member of the research team. He added: “The lithium is produced by nuclear fusion reactions that occur during the explosion. It is fascinating that physics on the smallest scale — atomic nuclei — determines the outcome of an astronomical explosion.”

And there is more. The team has gone on to determine that a fraction of these classical novae will evolve until they explode as supernovae of type Ia. These exploding stars become brighter than a galaxy and can be discovered at very large distances in the universe.

As such, they have then been used to study the evolution of the universe and were the supernovae used in the mid-1990’s to discover Dark Energy, which is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate. But what underlying stars are responsible for these supernova explosions has been a mystery so far.

Classical novae

The formation of the universe, commonly referred to as the “Big Bang,” primarily formed the elements hydrogen, helium and a little lithium. All the other chemical elements, including the majority of lithium, are formed in stars.

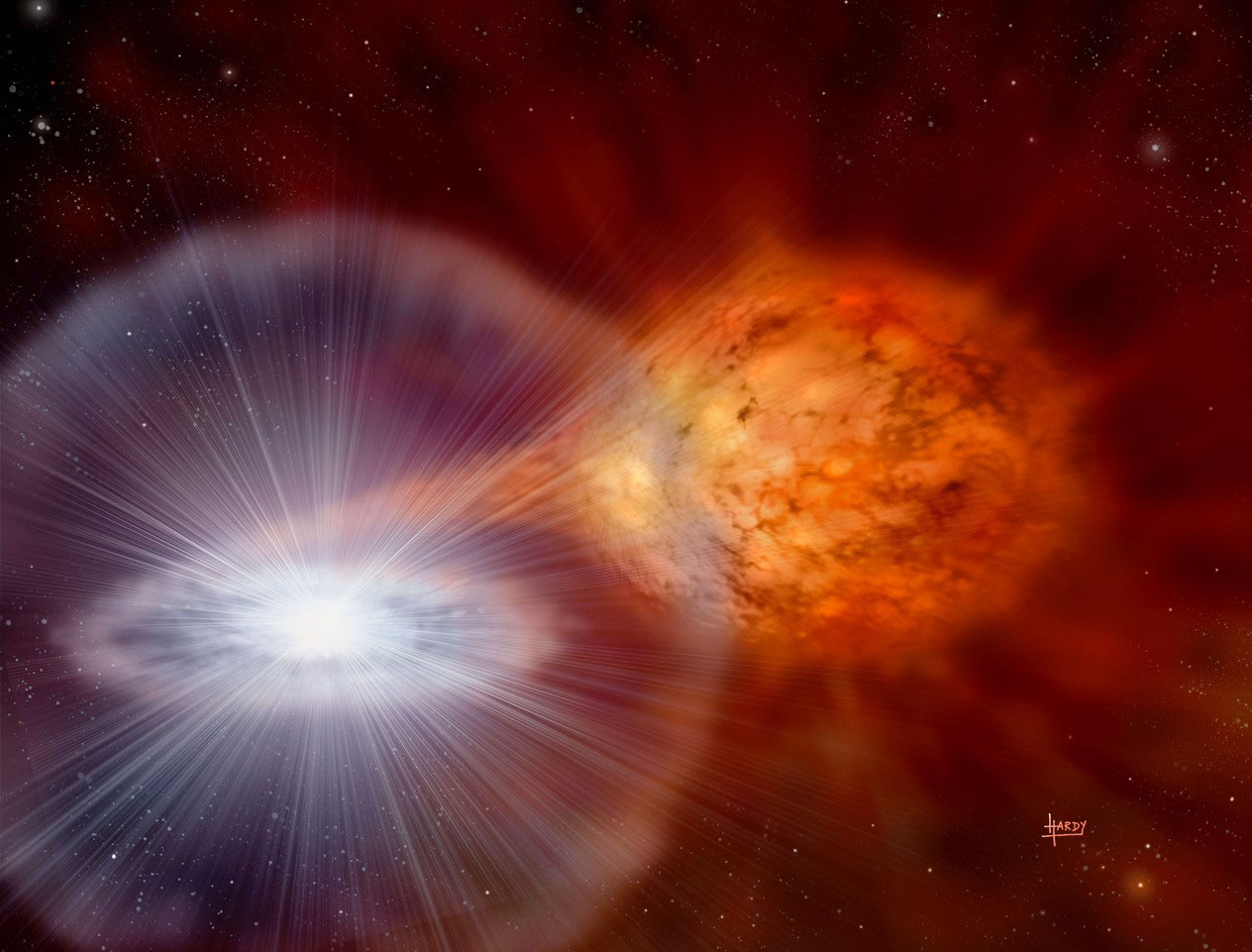

Classical novae are a class of stars consisting of a white dwarf (a stellar remnant with the mass of the sun but the size of Earth) and a larger star in close orbit around the white dwarf.

Gas falls from the larger star onto the white dwarf, and when enough gas has accumulated on the white dwarf, an explosion, or nova, occurs. There are about 50 explosions per year in our galaxy and the brightest ones in the night sky are observed by astronomers worldwide.

Simulations, observations and meteorites

Several methods were used by the authors in this study to determine the amount of lithium produced in a nova explosion. They combined computer predictions of how lithium is created by the explosion, how the gas is ejected and what its total chemical composition should be, along with telescope observations of the ejected gas, to actually measure the composition.

Starrfield used his computer codes to simulate the explosions and worked with co-author and American Astronomical Fellow Charles E. Woodward of the University of Minnesota and co-author Mark Wagner of the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory in Tucson and Ohio State to obtain data on nova explosions using ground-based telescopes, orbiting telescopes and the Boeing 747 NASA observatory called SOFIA.

Co-author Iliadis from UNC provided the numerical rates of the nuclear reactions that are a crucial ingredient for the computer simulations of novae. Many of these nuclear fusion reactions have been directly measured over the past decade at the local Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory, which is a U.S. Department of Energy “Center of Excellence.”

Co-author W. Raphael Hix of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and University of Tennessee, Knoxville, provided other insight into the nuclear reactions within stars that were essential to solving the differential equations needed for this study.

“Our ability to model where stars get their energy depends on understanding nuclear fusion where light nuclei are fused to heavier nuclei and release energy,” Starrfield said. “We needed to know under what stellar conditions we can expect the nuclei to interact and what the products of their interaction are.”

Co-author and isotope cosmochemist Maitrayee Bose of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration analyzes meteorites and interplanetary dust particles that contain tiny rocks that formed in different kinds of stars.

“Our past studies have indicated that a small fraction of stardust in meteorites formed in novae,” Bose said. “So the valuable input from that work was that nova outbursts contributed to the molecular cloud that formed our solar system.” Bose further states that their research is predicting very specific compositions of stardust grains that form in nova outbursts and have remained unchanged since they were formed.

“This is ongoing research in both theory and observations,” Starrfield said. “While we continue to work on theories, we’re looking forward to when we can use NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Telescope to observe novae and learn more about the origins of our universe.”

Story courtesy of Arizona State University