As the United States observes the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, scholars call attention to hard choices faced by suffragists that still influence voting rights today.

On Aug. 26, 1920, the 19th Amendment — proclaiming that a citizen’s right to vote shall not be denied on account of sex — became law, a week after the Tennessee legislature became the last state needed to ratify it, by a vote of 50-47.

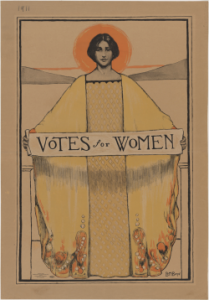

When they think of the 19th Amendment in this centennial year, professor Katherine Turk hopes her students will look beyond the romantic image of suffragists wearing white dresses with “Votes For Women” sashes and consider the hard fight it took to secure the vote – a fight that continues today.

“The 19th Amendment was the culmination of generations of feminists’ struggle and aspiration. They had to fight with hunger strikes and with very unladylike protests and marching in the streets. It’s a dramatic movement of women demanding to be included,” said Turk, associate professor of history and adjunct associate professor of women’s and gender studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. “It’s not like these enlightened male Congressmen just saw the light when women politely asked them to be granted suffrage.”

Another modern lesson of the 19th Amendment is that the struggle continues, especially for Black and Latinx women, Turk said. “We want to celebrate, but we have to be clear that this was one step in a very long story. Today’s efforts to limit suffrage are part of the story, too.”

Making the 19th Amendment relevant today is part of the Southern Oral History Program’s commemoration of the suffrage centennial (see Voting issues past and present below). Clips from archival interviews and new oral histories were combined to create a new K-12 teaching resource, while an article about the NC 2020 Coalition, a collaboration of women’s groups commemorating the centennial, will be published in the fall issue of Southern Cultures.

“Voting rights and voter suppression is an ongoing issue,” said Jennifer Standish, a doctoral student in the history department in the College of Arts & Sciences, who oversaw the oral history project. “Tracing the history of women’s suffrage and understanding the way that many women have actually been excluded is really important to understanding why this still is a problem.”

‘Remember the ladies’

American women have advocated for the right to vote since the country was born. One was Abigail Adams, who wrote to her husband (and future U.S. President) John Adams to “remember the ladies” when forging the new nation. The Constitution didn’t prohibit women from voting, but it didn’t guarantee their right either, leaving the particulars of who gets to vote to the states.

Most states decided to limit the vote to white men, often only those who also owned property.

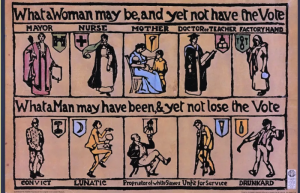

A woman’s place was in the home, and that’s where she reigned, the anti-suffragists reasoned. Why would she want to get involved in the dirty world of men’s politics?

“The anti-suffragists are fascinating from a modern perspective. And a lot of them were women,” Turk said. “They argued that by participating in the masculine act of voting, that women would forfeit certain gendered protections and privileges.”

Voting issues past and present

To commemorate the suffrage centennial, Southern Oral History Program came up with two related projects that call attention to voting issues past and present. In the first, undergraduate interns conducted oral histories to document the origin and growth of the NC 2020 Coalition, a collaboration of women’s organizations to commemorate the anniversary. The group’s purpose is to promote accuracy of the historical record, showcase legal and social advances in gender equality since the amendment’s passing and describe its relevance in the current fight for equal rights.

To accompany the oral histories, the program commissioned five original posters to counter the 19th and early 20th century suffrage posters in which women of color are not shown.

“Our hope that the artist/designer will turn these original designs on their head, using them as fuel to create new posters that honor all of the women who have sacrificed their lives for voting rights,” reads the call for entries. The selected posters will be rolled out in the weeks leading up to the 2020 election, to promote voter turnout.

Coalitions and fragmentation

Women’s suffrage became part of a larger progressive movement in America that brought together all kinds of reformers, including abolitionists and promoters of temperance. “There were all these different strands of activism, sometimes working together, sometimes working at cross-purposes. But women’s suffrage was a single goal that a lot of differently situated women could get behind,” Turk said.

After the Civil War, some suffragists saw the 14th and 15th Amendments as a way to secure women’s right to vote, even though these amendments were primarily concerned with granting citizenship and voting rights to people who had been enslaved. But their efforts were thwarted by one word in each — the first time the word “male” was used in the Constitution (in the 14th Amendment, to define voters) and the exclusion of the word “sex” in the 15th Amendment’s list of voter protections.

This effort to push women’s suffrage at the same time others were working on securing the vote for Black men (and other issues) created a rift in the suffrage movement. Women’s suffrage became entangled with white supremacy and discrimination against immigrants, as some suffragists argued that the white woman’s right to vote would counter the votes of Black men and working-class immigrants.

“The national suffrage movement eventually conceded to the Southern states because they needed the support of Southern states to succeed in the national arena,” Standish said.

Reclaiming history

White suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony dominated the movement and the writing of its history. The work done by Black suffragists like Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells as well as those who advocated for the rights of indigenous, Latinx, Asian American, immigrant and working-class women has been largely ignored.

“Tracing the history of women’s suffrage and understanding the way that many women have actually been excluded, not only from women’s suffrage but in the name of women’s suffrage, is really important in understanding why this still is a problem that people have to fight against today,” Standish said.

Perhaps the most dangerous part of the romantic version of the 19th Amendment story is its fairy-tale ending, that after its ratification all women lived (and voted) happily ever after, Turk cautioned.

“It’s a dangerous narrative because it suggests that we don’t need to be active citizens claiming those rights and protecting those rights and expanding those rights,” Turk said. “Democracy might be in a different place now if more white voters were alarmed by recent rollbacks to the Voting Rights Act. If we’re not thinking about each other, then all of our rights are in peril.”

By Susan Hudson, The Well