Bookmark This is a feature that highlights new books by College of Arts & Sciences faculty and alumni, published the first week of each month.

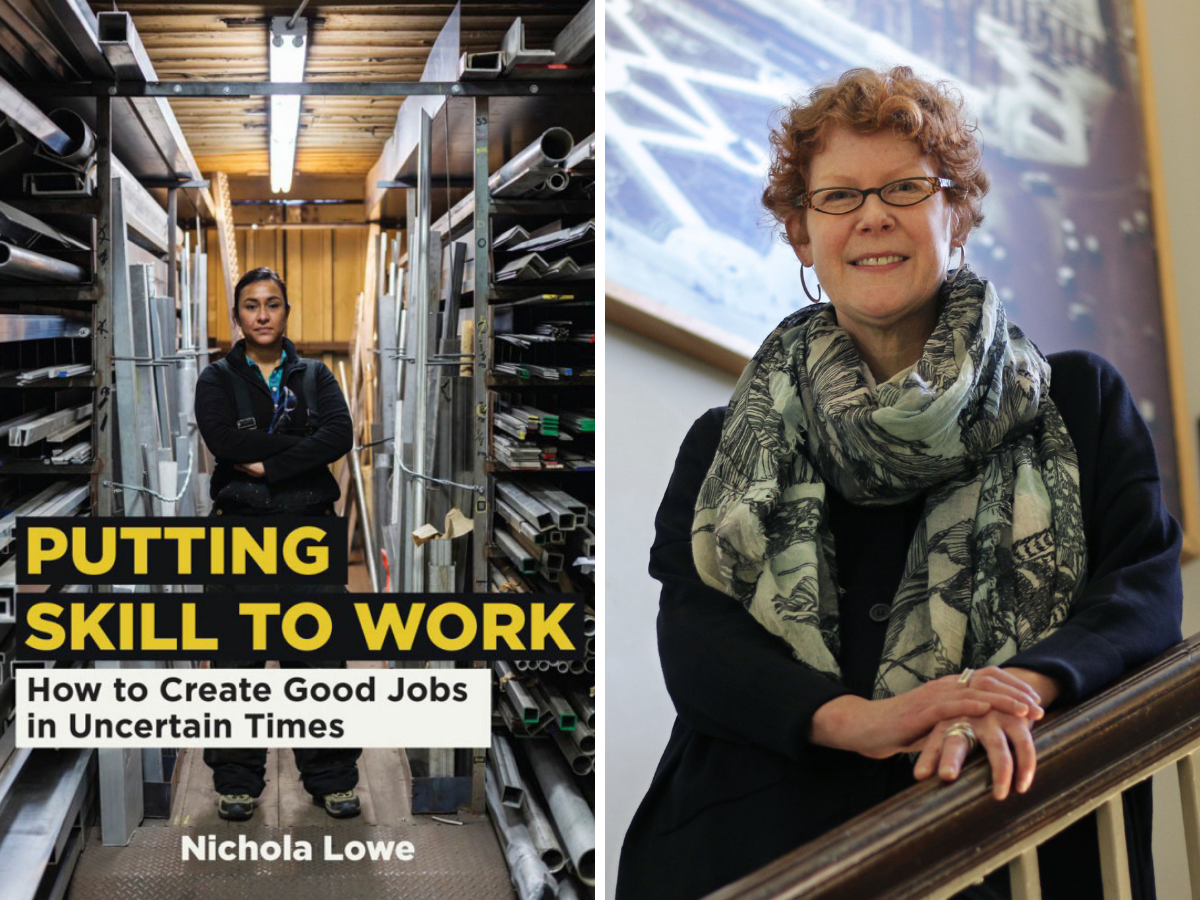

This month’s featured book: Putting Skill to Work: How to Create Good Jobs in Uncertain Times (The MIT Press, March 2021) by Nichola Lowe.

Q: Can you give us a brief synopsis of your book?

A: America has a jobs problem — one that predates the current pandemic recession. There are not enough good-paying jobs in this country to go around nor clear pathways leading to them. In this book, I argue the transformational power of skill is frequently misunderstood. Too often skill is narrowly equated with formal educational attainment or oversimplified through measurement techniques. The real power of skill actually lies in its uncertainty, reflected in the elemental yet enigmatic questions of who possesses skill, where it resides and whose responsibility it is to build it over time.

In my book, I feature pioneering workforce intermediaries — community-based organizations, union affiliates, publicly-funded community colleges — that recognize the power in skill ambiguity and harness it to extend economic opportunity to workers at the bottom of the labor market. These intermediaries become stronger advocates for workers by changing employer thinking around skill and also pushing more of them to make a greater commitment to supporting and rewarding skill development. As these intermediaries help employers reinterpret skill, they also convince them to implement inclusive work-based systems that extend family-sustaining wages and better working conditions across the entire workforce.

Q: How does this fit in with your research interests and passions?

A: Broadly speaking, my research seeks to make visible the hidden talents of workers, focusing especially on the knowledge contribution of workers that have not secured a college degree, whether at the bachelor’s or associate level. This workforce is frequently misclassified as “unskilled,” overlooking the complexity, ingenuity, creativity and essential contribution of their work. My book focuses on the frontline manufacturing workforce, but there are workers in so many other industries, from hospitality and health care to construction and agriculture, that are wrongly dismissed as unskilled or underqualified.

Q: What was the original idea that made you think: “There’s a book here?”

A: This book threads together various research projects developed over the past 15 years, some of which were independently conceived. I started to draw connections across different case studies and institutional contexts while teaching my graduate seminar, “Planning for Jobs” and a First Year Seminar version of it called “The Changing American Job.” This led me to conduct additional research, allowing me to further explore the complicated and uncertain relationship between skills, job quality and economic inequality.

A semester-long fellowship at the Institute for the Arts and Humanities was most critical in the project’s development. That helped me to realize a longer manuscript would offer an interpretative space for unpacking ideas and engaging emergent policy and disciplinary debates, also allowing me to reach new audiences well beyond planning and outside the university as well.

Q: What surprised you when researching/writing this book?

A: My last chapter explores technology and the future of work. I push back on the popular narrative that technological change, including advances in robotics, artificial intelligence and computing, will inevitably cause massive and permanent job loss. I ponder an alternative future where technology adoption will be institutionally mediated and thus cause less harm and disruption for workers going forward.

I was surprised to learn that labor unions do embrace rather than resist technological change. But that support reflects their ability to get ahead of technology deployment. An example is the Culinary Union in Las Vegas which collectively represents over 57,000 hospitality workers. In the mid-2000s, Vegas workers began raising concerns about the future impact of automation on casino jobs. In response, the Culinary Union added a technology pacing provision to their collective bargaining contract, requiring casinos to give the union a minimum of 180 days’ notice in advance of technology implementation. With this early warning system in place, the union gains time to investigate the potential impact of a technological change on the workforce and devise adaptive responses.

But the Culinary Union has gone well beyond technology pacing. They recently introduced an annual survey giving front-line workers an opportunity to inform technology adoption. The union’s first survey revealed two immediate technology needs for workers: battery-operated carts that housekeeping staff requested to reduce physical injury from pushing heavy carts down long hotel corridors. And second, GPS-enabled panic buttons that could be attached to or embedded in the uniform to protect workers, especially women, from sexual or physical assault.

With this survey and through other technology-focused actions, the union is pushing an inclusive innovation standard — one which leading research institutions like UNC-Chapel Hill should uphold. Frontline workers have deep knowledge of organizational routines and industry practices that can inform technology development and deployment, also enabling university-based researchers and innovators to focus their creative energy on co-producing technological solutions that enhance, rather than destroy, jobs and livelihoods.

Q: Where’s your go-to writing spot, and how do you deal with writer’s block?

A: I write best in the early hours of the morning when the house (or office) is quietest. I also budget a lot of time for rewriting and editing, especially as I embark on a new chapter or journal manuscript. For every hour of writing, I set aside at least two to three hours to edit. Having this precious editing time ultimately means I can protect my schedule and stick to daily writing goals.

Lowe is a professor of city and regional planning. Read more about the book.

Nominate a book we should feature by emailing college-news@unc.edu. Find previous “Bookmark This” features by searching those terms on our website, and add some books to your reading list by checking out our College magazine books page.