In Associate Professor Michelle Robinson’s American studies Maymester course, “Comedy and Ethics,” students explored how stand-up comedy enriches American culture and sparks ethical discussions, all while making people laugh.

Sometimes laughter is the best medicine.

Students in Michelle Robinson’s Maymester course, “Comedy and Ethics,” took their medicine by studying some of the funniest and most controversial comedians in American history. Robinson, an associate professor in the College of Arts & Sciences’ American studies department, has taught some iteration of “Comedy and Ethics” since 2016, but this Maymester was a unique chance to teach the course in a hybrid format.

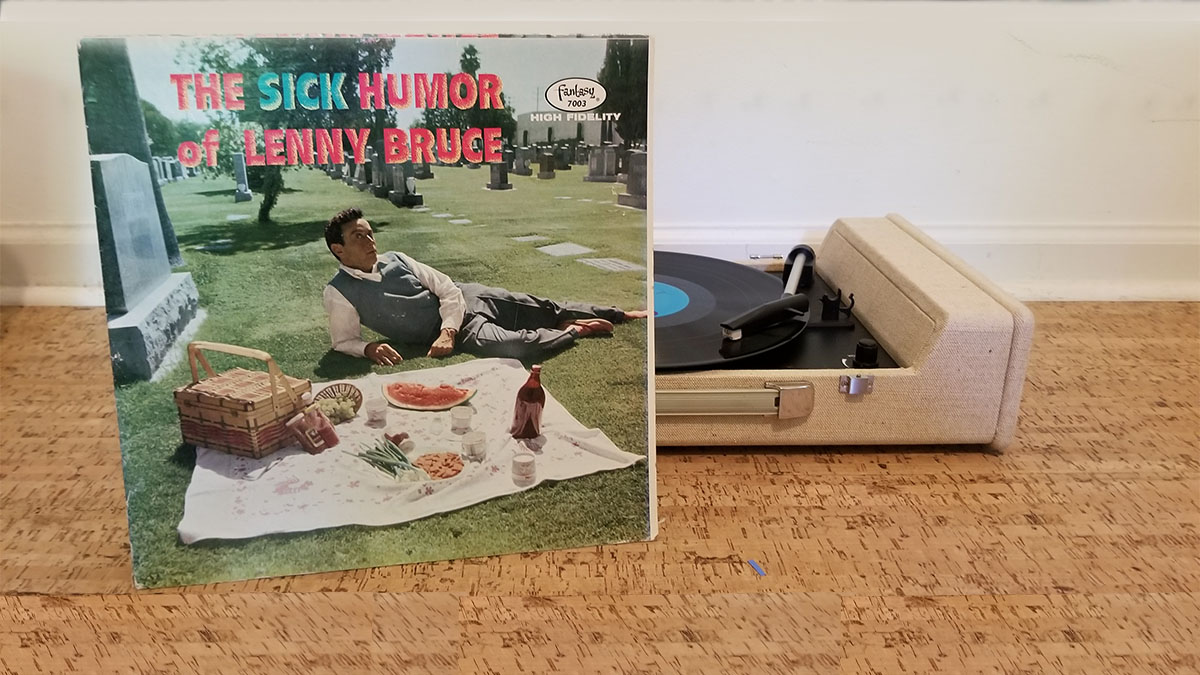

The three-week course explores the historical and cultural role of stand-up comedy in the American identity through scholarly articles, Netflix specials and even vinyl recordings of comedy albums by the greats of the genre. Some students in masks met in person and learned to identify laughs and facial expressions from the top halves of faces; others attended via Zoom. The entire class relearned what it meant to laugh together.

“Laughter can either cause affiliation or discomfort, and examining those results are where the best conversations start,” says Robinson. “When something makes us laugh, we should ask ourselves what made that particular joke funny and what does that say about us?”

The course approaches stand-up comedy as a type of cultural expression that exposes ethical questions that might not otherwise be asked. Robinson challenges her students to question the motivation and ethical concerns behind every joke and view comedians as social commentators.

“Comedians are asking some of the toughest ethical questions of our time, but since they make us laugh, we don’t always take their cultural critiques as seriously as we should,” Robinson says. “Studying comedy gives us the opportunity to dive into those ethical questions while laughing together.”

Robinson’s students started their comedy education by listening to and watching stand-up from the mid-20th century to present day.

‘A comic says funny things; a comedian says things funny.’

American comedy’s roots might surprise you: Netflix comedy specials of today owe a lot to immigrants trying out their one-liners on vacationers in rural New York state in the 1950s.

“Traditional stand-up developed out of vaudeville and created a space for entertainment cultivated by immigrants, including Jewish American immigrants,” Robinson says. “There were many comedians, like Lenny Bruce or Joan Rivers, who developed their work at resorts in the Catskills to become crossover comedians and enter a broader cultural sphere. Some humor studies scholars consider a mainstream American comic sensibility to be a Jewish invention.”

Moving forward, the range of comedians expanded in the 1960s to those who wrote their comedy to appeal to a broad range of audiences and achieve mainstream popularity while others put their comedy in service of social change. Two examples Robinson shares with her class are Bill Cosby, who is African American but presented himself as a wholesome comedian for the masses (and who has since been convicted of aggravated indecent assault), and comedian Dick Gregory, who was involved in the civil rights movement and used his comedy as a way of conveying political ideas and pushing the movement forward.

In the 1970s, comedian Richard Pryor became famous for his storytelling style of comedy and frank commentary on race in America. Teacher of Acting Samuel Gates from the College’s department of dramatic arts, an expert on Pryor’s work, visited Robinson’s class to discuss Pryor’s decision late in his career to stop using racial slurs. Pryor was an influential comedian who mentored many young comedians. Evaluating the effect (or lack of effect) his decision had on comedians who followed in his footsteps sparked discussion of the role of racial slurs in stand-up comedy.

Studying historical comedic styles and personas allows scholars like Robinson to track the influence of each generation on the next and show how modern comedians’ material is shaped by a rich stew of American comedic traditions. One example Robinson cites is how comedian Paul Mooney, who died in May, worked closely with and wrote for Richard Pryor and Redd Foxx, but also discovered Sandra Bernhard and Robin Williams.

What makes a joke funny?

The most “basic” unit of the stand-up form can be a structured joke, like a one-liner. For example: “I was wondering why the Frisbee kept getting bigger and bigger, but then it hit me.” Today, audiences are familiar with more diverse styles of comedy that tackle traditionally off-limits topics such as racism, sexuality and sexual assault, Robinson says. These jokes might complicate or clarify cultural values depending on a joke’s construction, articulation and the identity of the comedian.

The comedian’s identity also contributes to how a joke “lands,” says Robinson. Her students analyze the personas that comedians create onstage, including what they wear, their gestures, facial expressions, props and how they interact with the audience.

Robinson asks her students to think beyond the structure of a joke and the comedian’s identity and ask themselves, “Is this comedy inclusive or exclusive?”

Robinson also wants to clarify for anyone who’s wondering: A joke doesn’t make people racist, but it might make people who are already racist feel comfortable exercising their prejudice.

What’s funny about a pandemic?

This iteration of “Comedy and Ethics” was a unique experience for the students who made it through a pandemic and had the chance to learn to laugh together again. They became adept at reading signs of laughter behind their classmates’ masks and even practiced jokes together — for credit, of course.

Robinson says that while this Maymester was “too soon” for students to enjoy jokes about the pandemic, her students did feel more comfortable discussing the intersection of mental health and humor after experiencing the common trauma of the last year. The students’ favorite comedians this semester reflect that hunger for material that addresses mental health: Maria Bamford, Gary Gulman and Bo Burnham all address their struggles and/or experiences with therapy in their stand-up.

This year’s students participated in a new final project: writing to Chancellor Kevin M. Guskiewicz proposing a stand-up comedy festival to take place at the University. They used their knowledge from the course to explain how performances by their favorite comedians (both personally and from class) would serve the needs of students post-pandemic, rebuild the community and provide entertainment.

Next year, Robinson hopes to offer “Comedy and Ethics” again with an additional one credit course focused solely on practicing and developing a stand-up set. In previous semesters when the course was taught solely in-person, Robinson allowed students to perform a short set of stand-up comedy for their peers before the final exam with ground rules: no insults and no heckling. In future classes, she hopes to bring that tradition back, along with having a large group of students physically present and laughing together without masks or Zoom buffering to hinder the experience.

“Watching comedy performed by your peers right before you take an exam is a great encouragement, because then it doesn’t matter whether you’re failing the exam. At least you’re still laughing,” Robinson says.

By Madeline Pace, The Well