Upon discovering a series of political cartoons mocking artists in 18th– and 19th-century France in 2010, UNC-Chapel Hill art historian Kathryn Desplanque couldn’t stop searching for them. Now, she has amassed more than 500 and is using them to redefine how we think about art and the artist in modern-day society.

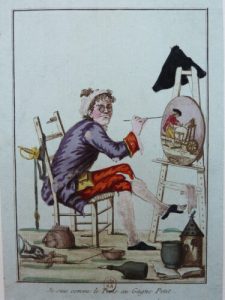

A one-shoed man wearing a slouchy hat and oversized shirt holds a match toward the wicks of a large black cannon aimed at two buildings. One is the French Panthéon — a mausoleum in Paris that houses the remains of distinguished citizens, including the writer Voltaire, philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Louis Braille, inventor of the reading and writing system with his surname. The other is the Institut de France, where the country’s greatest living cultural, political, and artistic minds reside.

But these cannons are not filled with gun powder. They have been stuffed with art prints and demons, which spill forth from the barrels. In the background, middle-class Frenchmen cheer on the man behind the mortar, excited to see his artistic creations in action.

This is a 19th-century French political cartoon. One of exactly 530 collected by UNC-Chapel Hill art historian Kathryn Desplanque.

“It’s a kind of shooting-myself-in-the-foot image of the artist,” Desplanque says. “He acknowledges being the maker of these objects and trying to have a career, but also that in making these objects he’s probably destroying his career.”

Desplanque has spent nearly a decade traveling to Paris and other cities in France to collect these unique and often obscure prints, most of which were made in the 18th and 19th centuries, from the depths of libraries and archives. On the surface, such objects feel far removed from modern-day culture in the States. But after spending some time with Desplanque, she reveals that they are a commentary on the artist that prevails even here and now.

“This research topic has less to do with 18th– and 19th-century political cartoons and printed images and more with my interest in trying to understand what art-making and the art world looks like in a capitalist society,” she shares. “I think the best example in popular culture is how we’ve accepted that to be an artist is to starve and struggle — and that trope is alive and well in how we make decisions about what our careers are going to be and what we are going to get degrees in.”

Going off the rails

Desplanque began her academic career as a maker of art rather than a historian. She majored in studio art at Concordia University and practiced printmaking and painting. Some of the things she saw as a student in the art world made her uncomfortable, like the idea of producing art to achieve financial success rather than personal fulfillment.

“Art school was so much more strategic than I imagined it was going to be, and there are some weird, secret ways that one can become successful as a contemporary artist,” she shares.

Politics, nepotism, networking, popularity. She thought the art world would be exempt from these social constructs, but quickly discovered that wasn’t the case. She found that friendships with curators and attending the “right parties” trumped talent. And while these realizations disturbed her, they also enthralled her.

After picking up a minor in art history, she took a class that introduced her to Pierre Bourdieu, a sociologist of art who interviewed people about their experiences within French art museums. He discovered that many of them visited these spaces to accrue social capital. In response to this knowledge, Desplanque began pondering how these seemingly subconscious hierarchies within the art world affect the way people create and think about art.

Desplanque went on to pursue a master’s in art history at Carleton University, where she discovered an “exceptional, slanderous image” of French painter Jean-Baptiste Greuze. This etching is a multi-pronged attack, according to Desplanque, that targets his ethics, relationships, artistic performance, and even his wife.

In 2010, Greuze’s caricature took Desplanque on a wild goose chase throughout Paris as she attempted to find another edition of the image — which was anonymous, undated, and untitled. In other words, the worst possible case scenario for an art historian. But the hunt only escalated Desplanque’s drive to find the image.

Eventually, she found herself in the prints and drawings room at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, peeling through a falling-apart collection of folios.

“It was a weird little rag-tag scrapbook of images,” she describes. “A collection of scrappy, anonymous, cheaply printed images that related to the arts in some ways.”

And there it was: a second edition of the Greuze caricature. But alongside it was a slew of other political cartoons.

“I totally went off the rails,” Desplanque admits. “I basically just stopped doing my M.A. research for weeks and was like, What is this? What are these images? What is happening? I was so surprised and interested and confused and enamored with them — and realized I needed to stop. I needed to go back to my M.A. research.”

Little did she know at the time that this caricature would be the first of more than 500 images that would lead to her PhD thesis and current topic of study: political cartoons from 18th– and 19th-century Paris that examine the relationship between artists, consumers and critics of art, and the art world more broadly.

Crafting her corpus

In 2014, during her PhD program at Duke University, Desplanque spent six months traveling across France in search of political cartoons. Much of her time was spent at the French national library and the Musée Carnavalet — a municipal museum of the history of Paris — but she also found a “strange collection of images” at the Musée de la Révolution française, located six hours southeast of Paris in Vizille.

“It was quite a dedicated hunt,” says Desplanque, who is a fluent French speaker, having attended a French immersion school as a child. “I spent days pulling out folios with hundreds of prints and finding only one or two interesting things — and then doing the same thing the next day and the day after that.”

Today, Desplanque’s collection — what she lovingly refers to as her “corpus” — has been digitized for easy access by other scholars. They are the subject of her first book, “Inglorious Artists,” which addresses the way visual arts mobilized political cartooning and graphic satire as a vehicle to criticize the emergence of a free market for art around a series of political and economic revolutions, including the Industrial and French revolutions, during the 18th and 19th centuries.

During this time, France experienced nearly six major governmental shifts in just 60 years, and that instability drastically affected the art world. For most of the 18th century, any artist who wanted to make a living from their craft needed to belong to a government-sanctioned guild — which, like Desplanque’s experience as a studio art major, both appalled and intrigued her. But in 1776, that law was repealed and, for the first time, any artist in France could make art without guild membership.

“I spend a lot of time in my book belaboring how wild this would have been,” Desplanque says. “One day, you needed to navigate a very ornate and complex institutional system just to make art, bring it outside, and try to sell it without having a group of thugs beat you up, take your art, and confiscate it. The next, you could make art and traffic it whenever and however you wanted. That happened within a space of 24 hours. That system you had always known, that your parents had always known, that your grandparents had always know, suddenly shifted.”

And the image of the starving artist starts to emerge in France. The events of 1776, Desplanque believes, spurred the rise of new artists and growth of the art market. Supply began to eclipse demand, and artists began to worry even more than they already were about making ends meet.

The political cartoons that erupted at this time characterized artists, and patrons, in a multitude of unflattering ways. Desplanque’s collection includes images of the artist romancing their model, art students depicted as irresponsible rakes, artists who care more about how they’re dressed than what they’re making, bourgeois patrons making ridiculous demands of their portrait painter, and a gawking audience at an art exhibition, ogling artworks and making ignorant comments about them.

“We start to see this mockery of notions of Romantic genius, and just making fun of this idea that the artist lives against the grain of society,” Desplanque says. “The artist wakes up late. They don’t follow a normal schedule. They are terrible parents. They are narcissistic. They don’t pay attention to the people around them, to the people who depend on them. They’re very dedicated to their artistic creation and their vision and are unconcerned with whether they’re making work that somebody actually wants to consume or view or buy. I see this quite a bit in satire, sort of pointing out that the artist is neglected.”

A slew of other tropes abounds. The drunken artist who’s always scheming to get somebody else to pay for their life. The bohemian artist, boldly opposing the fashions of society, growing out their beard and wearing clothing from previous centuries. The bourgeois patron who only appreciates art for its decorative value or exclusively commissions portraits out of self-obsession and vanity.

“The implication is their patronage will destroy the arts,” Desplanque says. “That nobody will have the opportunity to make great art anymore if they only make art for this buyer.”

Redefining art

Desplanque continues to see these tropes today in the way society depicts artists and defines what qualifies as art. In her art history classes at UNC, she often asks students to consider memes and selfies as visual objects to get them to think about what we deem as “high art” and why.

“Visuality surrounds us, and it’s all quite intentional and worthy of consideration,” says Desplanque.

She turns and looks at her office.

“Those potted plants. The prints on the wall. This desk. We are constantly encouraged to reinforce these divisions in what we decide we’re going to think of as an art object and what we decide we won’t. And a lot of that has to do with institutions and spaces that constitute an art world.”

Many of us have been taught that to experience art we have to visit museums. We have to remain quiet while moving in slow concentric circles. We have to read all of the text that accompanies a piece. We have to allot so much time to each piece to truly ponder its meaning.

But Desplanque thinks spending the same amount of time looking through your Instagram feed is just as meaningful. When you think about it, are the artists who promote their work on social media any different from her French political cartoonists?

At the end of our conversation, Desplanque reflects on the cartoon of the artist about to fire his cannon full of artwork at two of France’s most historic buildings.

“I think he recognizes the disservice to his career he’s trying to have by being a political cartoonist,” she says. “But I have to wonder if there was a satisfaction that came from finding an environment where he was known to a wider audience for his insightfulness, his expertise, his abilities, his artfulness.”

Kathryn Desplanque is an assistant professor within the Department of Art and Art History within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences. She is a former Carolina Postdoctoral Fellow for Faculty Diversity.

By Alyssa LaFaro, Endeavors