Five years in, the innovative policy model has proven enormously effective at turning state funds into life-changing research.

Jeff Warren remembers the moment the North Carolina Collaboratory turned the corner, when he thought, Yes, this is going to work.

It was the summer of 2018, and the North Carolina General Assembly had just appropriated $5 million for a statewide study of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), including GenX, a potentially toxic industrial PFAS compound detected in the Cape Fear River.

“That was our first large-scale project involving multiple universities,” said Warren, the Collaboratory’s executive director. “That was when I knew we were going to be called on by our legislature to address complicated issues in North Carolina that required scientific research. But I also knew that we had to perform because that was, and continues to be, such a high-profile issue.”

Perform they have.

With that money and additional appropriations, not to mention the millions of federal grant dollars leveraged by these investments, the Collaboratory created the North Carolina PFAS Testing Network, comprised of principal investigators from seven universities — Duke, East Carolina University, NC A&T State University, NC State University, UNC-Chapel Hill, UNC Charlotte and UNC Wilmington.

Nineteen different researchers on eight teams put a full-court press on the PFAS problem. They conducted water sampling, air sampling, private well risk modeling, PFAS removal testing and more.

Work by Carolina chemist Frank Leibfarth and engineer Orlando Coronell led to a promising new ionic fluorogel resin that removes PFAS from water at a far greater efficacy than other available technologies. The legislators were so impressed they recently made an additional $10 million investment in scaling up the resin technology for testing under real-world conditions at water and wastewater treatment plants.

The PFAS response serves as the perfect example of why the General Assembly created the NC Policy Collaboratory in 2016 — to put the research expertise of the University of North Carolina System to work for the benefit of the state. In 2020, the legislature permitted partnerships with private colleges and universities. Since then, the name was shortened to NC Collaboratory.

“The North Carolina Collaboratory is unlike any other research center that’s been created by any university.”

— Al Segars, NC Collaboratory chair, PNC Distinguished Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship, Kenan-Flagler Business School

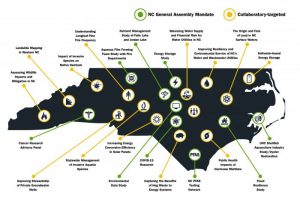

Headquartered at Carolina, the NC Collaboratory conducts both legislatively mandated research, like the PFAS work and a diverse portfolio of COVID-19 related research, as well as ideas that originate from Collaboratory staff and advisory board members, including landslide mapping in Western North Carolina and the public health impacts of Hurricane Matthew along the coast.

At the beginning of February, the NC Collaboratory marked its five-year anniversary with a report recapping its many successes and looking ahead at what’s next.

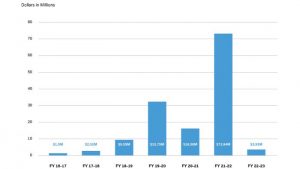

To date, the Collaboratory has or will soon fund more than 300 projects across all 17 campuses in the UNC System. It has received more than $145 million in legislative appropriations — funding that otherwise would not have entered the UNC System. More than half of that total came from appropriations made in last November’s state budget, another vote of confidence from the General Assembly.

For Warren, however, who has a doctorate in marine geology and geophysics from Carolina and spent 15 years doing state-level science policy work in North Carolina, the clearest stamp of approval came when the legislature voted in November to codify the Collaboratory.

“Before, our authorizations and directives were spread across numerous session laws,” Warren said. “Now, we’re codified. When you take down the big green statute books from the shelf, we’re there in article 31a of General Statutes 116-255. Those are the laws that establish the UNC System. The NC Collaboratory is now part of that.”

Nimble, efficient, fast

Before the NC Collaboratory, plenty of research at Carolina and other UNC System schools addressed practical issues in the state. So how is the Collaboratory different?

“What makes us unique is that not only do we utilize the full 17 campus system, but the business flow we established to be nimble and efficient and allow for a quick-response to real-world issues and opportunities has been the key to our success,” Warren says.

For one thing, Collaboratory projects don’t pass through the Office of Sponsored Research. Instead, the Collaboratory works directly with principal investigators. As an example, Warren points to flooding caused by Hurricane Florence in September of 2018.

“While the water was still high, we had an opportunity to send researchers into the field and grab samples to identify what was in the water, to get a set of data points that wouldn’t be available a week later after the water receded,” he said. “We had a conference call in the morning. We created scopes of work and budgets, and the researchers had funding agreements signed that afternoon. The next day, we transferred the money.”

Tailor made to tackle a global pandemic

Time was certainly of the essence when COVID-19 hit.

“Often, federal and state funding sources are behind the wave. NC Collaboratory funding has allowed my research laboratory to be in front of the wave,” said Rachel Noble, Mary and Watts Hill Jr. Distinguished Professor of Marine Science in the College of Arts & Sciences’ Earth, marine and environmental sciences department. In the spring of 2020, the Collaboratory funded Noble’s wastewater-based coronavirus surveillance project. “It was not until several months later that CARES Act and other funds to support COVID-19–related research were available. By then, our laboratory had completed and was underway with standardized, streamlined, optimized approaches, and gaining traction with state and federal agencies.”

The NC Collaboratory seemed tailor made to tackle the global pandemic.

Relatively little was known about the novel coronavirus in May 2020, when the General Assembly awarded the Collaboratory $29 million to fund research focused on treatment, community testing and prevention of COVID-19. By July, the Collaboratory had funded 85 projects across 14 UNC System schools, including $1 million allocated to each of the six historically minority-serving institutions.

More than 40 of those projects involved research at Carolina. Some of the money went toward the Rapidly Emerging Antiviral Drug Development Initiative (READDI). Other funding went toward a convalescent plasma trial to understand how COVID-19 positive antibodies in plasma could be donated to prevent disease and death.

In March of 2021, the state awarded the Collaboratory another $15 million for COVID-19 research. All that money went toward genetic sequencing equipment and research to identify emerging variants and understanding how they respond to different therapeutics and vaccines. The result, developed in partnership with the NC Department of Health and Human Services, is a fully operational statewide variant sequencing surveillance network known as CORVASEQ (CORonavirus VAriant SEQuencing) that includes 12 academic and non-academic partners and 67 hospitals. CORVASEQ provided the state with a more consolidated surveillance tool through surges associated with both delta and omicron variants of SAR-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

November’s state budget added another $30 million in COVID-19 funding, plus more than $46 million for non-COVID-19 projects.

NC General Assembly appropriations

One of Warren’s favorite non-COVID-19 projects was a study to help bring back the oyster industry in North Carolina. The findings continue to change state policy. “It’s leading to more oysters being grown in our sounds and more North Carolina oysters in our restaurants, which means more jobs, more income and more state income tax,” Warren said. “And the more oysters in the sounds, the cleaner the water, because of the filtration they provide. That’s win-win-win.”

“Carolina has always received significant support from the leaders and citizens of our state, and their investment in the NC Collaboratory fuels one of the most critical ways that our University returns the favor: by finding solutions to the grand challenges of our time,” said Chancellor Kevin M. Guskiewicz. “I was dean of the College of Arts & Sciences five years ago and advocated for bringing the program to Carolina but never imagined it could have had this much success in such a short period of time. The Collaboratory’s work is having a significant impact across our state, and as chancellor I’m committed to continuing to support Jeff and his team.”

A model for the country

Warren calls the first five years of the NC Collaboratory a proof of concept for a model unique to the nation. Now, more than ever, he’s confident the model works.

“The Collaboratory is a very progressive and effective approach to science policy,” he said. “At some point, people are going to start coming to us from other states saying, How did you do it? We want to do the same thing.”

“I think one of the most exciting parts of this Collaboratory is the opportunity to get real time answers to questions that are really important and bringing together a really phenomenal group of people to solve problems in North Carolina. [The NC Collaboratory is] a model not just for North Carolina but a model for the country.”

— Barbara K. Rimer, dean, Gillings School of Global Public Health

The next five years are all about growth — not necessarily in terms of more money, but by staffing up, making more connections with researchers around North Carolina and doing more to communicate with stakeholders to find out about needs and opportunities.

“At the end of the day, we’re a public university system,” he said. “We belong to everybody in this state, and we should be in service to this state. I think we do a good job with that. It’s woven into the fabric of our philosophy.”