Students in a hands-on anthropology course piece together ancient ceramics, learn to fire pottery and cook with pots over a fire to study the history of pottery.

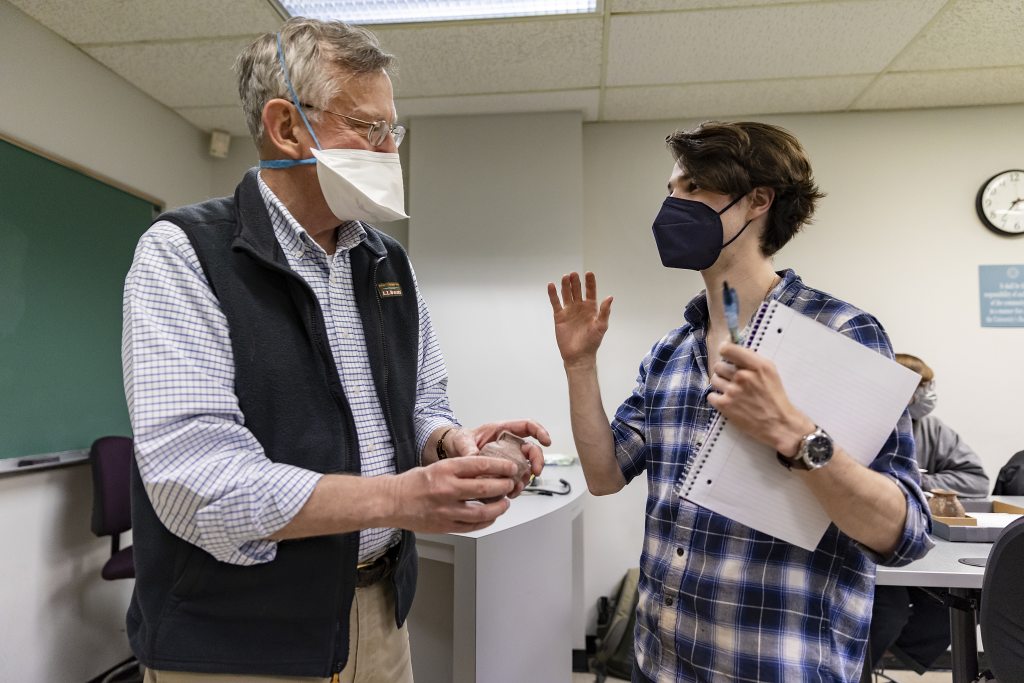

In one semester, anthropology students in “Lab Methods: Ceramic Analysis” course learn more about the history of pottery than many learn in a lifetime.

This spring, Anthropology 418 students visited a master potter, created their own pots, cooked over a fire and held pieces of pottery that were thousands of years old.

“Many archaeological interpretations are based on pottery, and this course gives them an understanding of how ancient pottery was made, how it was used, and what one can learn from the fragments one finds archaeologically,” said Professor Vin Steponaitis.

The class traveled to Pittsboro in February to visit Mark Hewitt, an artist who creates wood-fired, salt-glazed pottery. Hewitt walked the students through the creative process, including collecting clay from the earth; molding pots, plates, cups, bowls and art pieces; glazing the clay; packing the kiln; and firing.

“I love the experiential part of this course, the fact that it’s not just me talking to students and explaining to them something in the abstract but figuring out ways that they can learn and observe hands-on, like watching Mark [Hewitt] turn a pot or walking inside his kiln,” Steponaitis said.

A visit to the UNC Art Lab in Hanes Hall allowed the students to watch a different method of pottery making called coiling, where Joe Herbert, a retired archaeologist and skilled potter, rolled clay into coils and placed one on top of the other, forming a vessel with thick, durable walls.

In April, the class used the replica pots they saw created to cook a meal over a fire. Lecturer Rachel Briggs, who studies foodways, instructed the students on how to cook traditional hominy and other recipes by setting up charcoal pits and placing pots with the ingredients inside to cook over the coals.

“My favorite field trip was when we got to try cooking traditional recipes over open fires outside,” senior anthropology and history major Madison Brinkley said. “It was basically a cooking and archaeology lesson rolled into one, and each group made a different recipe, so I got to try lentils, stews and hominy all prepared the same way cultures we studied made them.”

Even without leaving the classroom, Steponaitis’ students applied what they learned in lectures by creating and handling pottery.

The class practiced identifying the materials and age of pottery by examining pots and shards in the classroom and writing reports on their observations. Some of the objects were simply broken pieces from Hewitt’s studio, and others were ancient.

The class used clay to sculpt their own earthenware pots and fired them outdoors. Brinkley said the experience helped her understand the production and contextualized the shards of pottery she examined in class.

“Most of us had no or very little experience doing pottery, so it was really useful for us because as archaeologists, we need to know how what we’re studying was actually made and to get into the craftsman’s mind a little bit,” she said.

“It’s kind of mind-boggling that I walked into the classroom and picked up a shard of pottery that’s 1,000 years old,” Brinkley said. “On the day we studied decorations on several different types of pots, I got to hold one from ancient Egypt, which is not an opportunity I thought I would ever have as an undergraduate.”

Joseph Harris, a junior classics major and aspiring archaeologist, said the course gave him additional hands-on experience with identifying pottery before joining the University’s archaeology field school in Hillsborough this summer.

“We’re studying the tools of people who laid the foundation for us,” said Harris. “We’re standing on the shoulders of giants, so when we’re excavating their possessions, we’re sort of excavating ourselves. And that’s why I find archaeology so meaningful.”

After teaching the course for more than 30 years, Steponaitis says making Anthropology 418 experiential is key to creating a solid foundation for future archaeologists.

“Carolina is a research university, and research and teaching are inextricably linked, which is especially true in archaeology,” Steponaitis said. “Archaeology is always done in teams, and those teams usually involve students, both undergraduate and graduate students. This course is just one example of the experiential opportunities that you should find across all archaeology pursuits.”

By Madeline Pace, University Communications