During his 60 years in Chapel Hill as pastor of Binkley Memorial Baptist Church and in retirement, Robert E. Seymour Jr. was a champion of social justice who led a congregation that challenged racial segregation and advocated on behalf of the aged and poor.

Seymour died in 2020 at age 95, leaving a gift in his estate to the College of Arts and Sciences. His children, Frances Jane Seymour ’81 and Robert E. Seymour III, directed the gift to causes that he cared so much about throughout his life, thus establishing the Dr. Robert E. Seymour Jr. Dean’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Fund.

The Seymour Fund will provide support for the dean to promote diversity, equity and inclusion efforts across the College of Arts and Sciences. A second portion of the gift will be used to support the same purpose through the Arts and Sciences Fund, the dean’s discretionary fund. With these two sources of funding, Seymour’s gift will provide vital support to the senior associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion in the College and expand DEI programming for both students and faculty.

“The spring is the dream of an inclusive society becoming a reality, and I think we are moving toward that. I’m optimistic about the future and feel that some of the racism that now erupts may be the death rattle of a dying culture.” Robert Seymour

Seymour’s ties to Carolina were strong. The young pastor and his wife, Pearl, who was the church organist, moved to Chapel Hill from Mars Hill, North Carolina, in 1959. The congregation of the newly founded Binkley Baptist Church met on campus in Gerrard Hall until 1965 when the church moved into its current location on Willow Drive in Chapel Hill. UNC had desegregated in 1955. By 1960, about 30 Black students attended UNC, with at least 12 worshipping at Binkley.

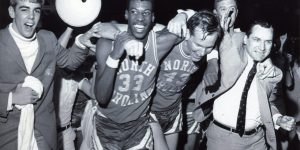

For nearly 30 years, he pastored legendary UNC basketball coach Dean Smith. The story goes that when Coach Smith was teaching Bible class at Binkley Baptist in the 1960s, Seymour gave him an assignment to desegregate the Tar Heel men’s basketball team. In 1966, Smith made good on this assignment when he recruited Charlie Scott, UNC’s first African American scholarship athlete. Although Seymour was not a huge sports enthusiast, his wife was a die-hard Tar Heel fan, and they regularly attended games. The couple also enjoyed taking in music and theater performances on campus.

As a pillar of the Chapel Hill community, Seymour recruited church deacon Fred Ellis in 1961 to run for the Chapel Hill-Carrboro School Board to work on integrating the town’s segregated public schools. After being elected, Ellis cast the deciding vote on integration in 1963 and the schools became fully integrated in 1966. In 1962, the Student Interracial Ministry of Union Theological Seminary in New York ran a program to place students of color in white congregations as interns and vice versa. Through this program, Rev. Dr. James A. Forbes Jr., now senior minister emeritus of Riverside Church in New York, came to Binkley as an intern. No other church in the area would accept a Black student.

“You might have felt as if you were his relative,” Forbes said of Seymour in The Daily Tar Heel. “It’s a very unusual thing for Black people to experience white people where the issue of race becomes insignificant in your exchanges.” In 1969, Seymour recruited Howard Lee to run as the town’s first African American mayor, a race he won. “There were a lot of progressive people who thought that my running would disrupt Chapel Hill, which was recovering from some of the nastiest battles that any town had experienced,” said Lee in Chapel Hill Magazine. “But [Seymour’s] blessing got people on board.”

Seymour worked tirelessly on behalf of the people of Chapel Hill and Orange County. He served as founding president of the Inter-Faith Council for Social Service, the primary provider of social safety net services in Orange County. He formed Habit for Humanity of Orange County in 1984 in partnership with his church, was active in People of Faith Against the Death Penalty, campaigned to build what is now the Robert and Pearl Seymour Center, which promotes the well-being of those age 55 and older in Orange County, and served on the board of directors for UNC Health Care after observing that older African Americans were going bankrupt because of medical debt.

Seymour’s charitable gift to UNC funds a continuation of that path.

“This gift that Dr. Seymour made to the College will be used to honor his commitment to demanding equality for all, by providing funding to support Karla Slocum, senior associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion in the College of Arts and Sciences, and to expand programming related to these efforts,” said Jim White, dean of the College. A portion of Seymour’s gift was put to work immediately to fund grants to 13 departments in the College to expand their equity efforts. A grant to the biology department, for example, provided support for diverse speakers and research related to the retention of Black biology majors.

“We are so thankful for the Dr. Robert E. Seymour Jr. Dean’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Endowment Fund,” Slocum added. “Given Dr. Seymour’s lifelong dedication to inclusion, anti-bias and social justice, it is an honor to receive this generous gift that will move our work forward in the College.”

When asked what her late father would have liked to see happen with his gift to UNC, Seymour’s daughter Frances said, “He would be happy to see these DEI efforts in the College — he always wanted to create spaces in the broadest sense to overcome biases toward race, sex, sexual orientation, age and beyond.”

His son Rob added, “Dad wanted to see this history kept alive. To show how difficult making change was — and still is. He always felt that if we keep plugging along, change for good will happen. He always looked on the bright side.”

By Andy Berner