The Education Policy Initiative at Carolina (EPIC) in UNC’s College of Arts and Sciences is keeping notes on how many teachers and principals are leaving the profession. The data details a worrying situation in the state’s public K-12 schools.

When the pandemic started and children stayed home from school, there was a congenial consensus that teachers should be recognized and appreciated for the roles they serve in society. Fast-forward nearly three years and that fuzzy feeling is diminishing, despite the increased need for dedicated educators. This anecdotal view of teaching in North Carolina is backed up by data from the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina (EPIC), which shows that teacher attrition is higher now than before the pandemic.

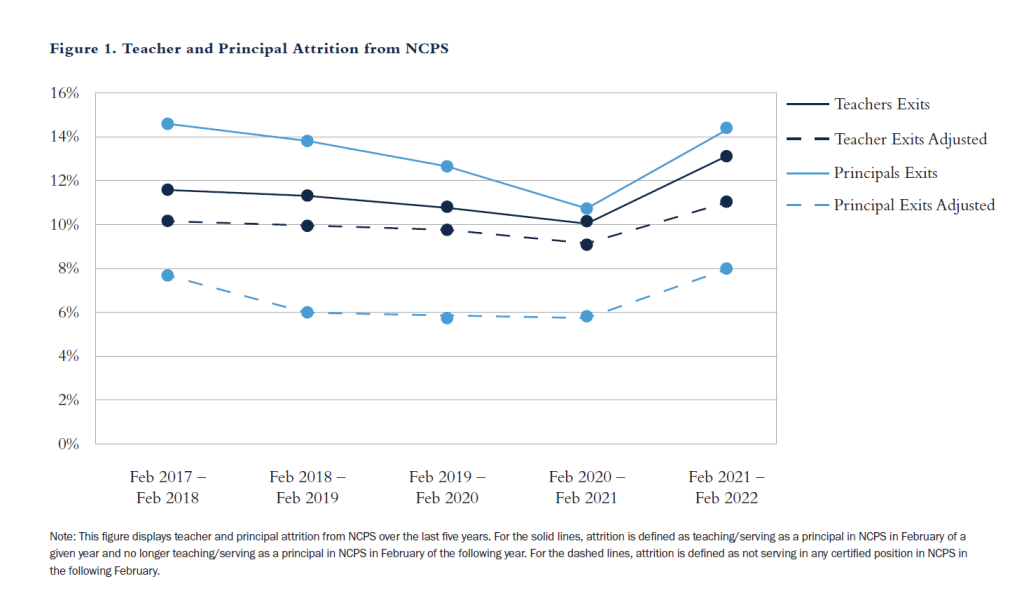

Researchers analyzed statewide data on all teachers and principals in traditional N.C. public schools (NCPS) in the 2016-17 through 2021-22 school years. This includes demographics, credentials, and measures of performance on nearly 95,000 teachers and 2,500 principals. In the three school years leading up to 2020, the percentage of teachers and principals leaving the state was getting smaller and dipped even lower during the first year of the pandemic. Teacher attrition from NCPS fell from just under 12% in 2017-18 to 10.3% in 2020-21. The rate of new hires for teachers slowed down as well, yet another reflection of an overall decrease in resignations.

“Attrition was down across the board during the first year of the pandemic,” says Kevin Bastian, director of EPIC. “The numbers we saw in our state fit with data from across the U.S. and in other professions. Fewer people were leaving their jobs in general in the early stages of the pandemic.”

“Attrition was down across the board during the first year of the pandemic,” says Kevin Bastian, director of EPIC. “The numbers we saw in our state fit with data from across the U.S. and in other professions. Fewer people were leaving their jobs in general in the early stages of the pandemic.”

But the percentage of teachers leaving NCPS jumped above 13% in the 2021-22 school year. That equates to an additional 2,800 teachers leaving the state education system compared to the prior school year.

“You hear lots of stories about burnout and stress with educators,” says Sarah Crittenden Fuller, an EPIC researcher. “It doesn’t look like teachers are leaving our state to go teach in another state. The difficulty of teaching during the pandemic is causing them to leave the profession all together.”

North Carolina schools were struggling to fill certain teaching positions before the pandemic. Because of this, the increased attrition is putting even more pressure on existing teachers, staff, and leadership who were already strained.

“You can’t have empty classrooms, and you can’t have unsupervised classrooms,” Fuller says. “When you have other staff members filling in for teacherless classes, their roles suffer, and children are impacted by the lack of consistency.”

Children have been heavily affected by instability over the past several years. The average U.S. public school student in grades 3-8 lost the equivalent of half a year of learning in math and a quarter of a year in reading, according to the Education Recovery Scorecard. At the same time, students have increased emotional needs. Teachers are challenged to catch up on lessons while also providing more individual support — a feat for even the most seasoned educator.

A nuance to the increase in attrition is that the percentage of new hires has generally kept pace with the percentage of exiting teachers — although a large percentage of incoming teachers are limited in experience.

“Early-career teachers are on average less effective than more experienced educators,” Bastian says. “It’s not just about filling a position, but filling it with a teacher who is well-equipped for the challenge.”

The same goes with school leadership. The pattern of principal attrition has mimicked that of teachers, but the rate of turnover in this group is higher. Over the last three years, the percentage of principals leaving the profession has gone from 12.6% leading into the pandemic, down to 10.6% in the 2020-21 school year, and back up to 14.5% in 2021-22. A lack of experienced and established leadership for schools and districts creates its own set of issues.

“There is damage to overall school stability and operations without proper leadership,” Bastian says. “There are also financial costs involved with hiring new personnel in these positions. Replacing these employees is costly for NCPS.”

Bastian and Fuller are now digging into the “why” of these numbers: why more novice, high-achieving, and teachers of color are leaving the profession, and why teacher attrition rates in schools serving more versus fewer low-income students and students of color have narrowed during the pandemic. But there is something this data makes clear to these researchers who also have school-aged children: More help is needed from the education system and parents to change this trend.

“Students need more now, so teachers are taking on more than ever,” Bastian says. “States, districts, and schools have a responsibility to make sure teachers and leaders have the resources they need to feel supported. There should be mentoring, professional development, and adequate compensation and benefits available.”

“We should realize the strain teachers and principals are under,” Fuller says. “Anything parents can do to make it easier, or at least not harder, would be helpful.”

Kevin Bastian is the director of the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina and a research associate professor in the Department of Public Policy within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences and principal investigator for the Educator Quality Research Initiative.

Sarah Crittenden Fuller is a researcher at EPIC and a research associate professor in the Department of Public Policy within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences.

By Carleigh Gabryel, UNC Research