The Carolina English professor talks about failure, the value of walking and the origin of his life-changing “napkin doodles.”

Drawing on his self-described stubborn march toward writing success, Daniel Wallace hopes to inspire graduates at the University’s Winter Commencement on Dec. 11 to find their path toward a meaningful life.

Wallace is known for his novels, including “Big Fish,” which was adapted as a movie and Broadway musical. Also an essayist and illustrator, he is the J. Ross MacDonald Distinguished Professor of English in the College of Arts and Sciences and, until recently, directed the Creative Writing Program for 11 years.

The Well caught up with Wallace on a recent walk to learn more about him.

Why do you like to walk?

During COVID quarantine, I was, like everyone else, mostly homebound. That’s when I got into walking. It provided a sense of exploration and escape and it allowed me to think, to work out problems with my writing, also to listen to podcasts, music. I started walking then and haven’t stopped. I’m so far away from home now I may never get back.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, I’m a goal-oriented person. I have a goal for words to write in a day, a goal for steps in a day. It’s really gratifying when I hit 15,000. It’s not a lot, but it keeps me sane and keeps my blood pumping.

That’s 15,000 words, right?

Ha! I’m much slower on the computer than I am on the trails.

You’ve talked about a unique path that each writer takes as opposed to more structured paths of lawyers and doctors. What’s been the best part of your path?

Well, I’m stubborn, and it’s gratifying to see that stubbornness pay off. I had a goal to publish a novel, and after 15 years, I finally did it. I was almost 40, which is not so bad. It’s not a race to see who can write the best book first. But I had been trying since I was about 24, so getting to this place where I could say without embarrassment that I was a writer, officially a writer, that has probably been the most gratifying moment for me.

When my first book was accepted for publication, I thought that I would be happy for the rest of my life. I didn’t think there was anything that could ever happen that would diminish this sense of satisfaction that I had. And it did last. I got a solid five days of happiness in before I stubbed my toe, and then everything fell apart.

You’ve described the five or six unpublished novels that you wrote early on as “really bad.” What did that really bad work teach you?

I read a lot before trying to become a writer, and I felt like I had read so much that it was all inside of my brain and that I should be able to summon what I’d learned through my reading and somehow apply it to what I was writing. But it doesn’t happen like that. It’s really trial and error, especially if, like me, you didn’t go to graduate school. It’s a process of learning what works and, more importantly, what doesn’t work.

There are so many paths through the forest. You’re just trying to get from one place to another but there are many dead ends, many brambles, many bears you may encounter. You go back to the beginning and take a different path. And when you’re discovering that or trying to discover that, it sometimes takes a long time.

How and when did you begin drawing? What sparked the thought that, My drawings could be illustrations for books and other projects?

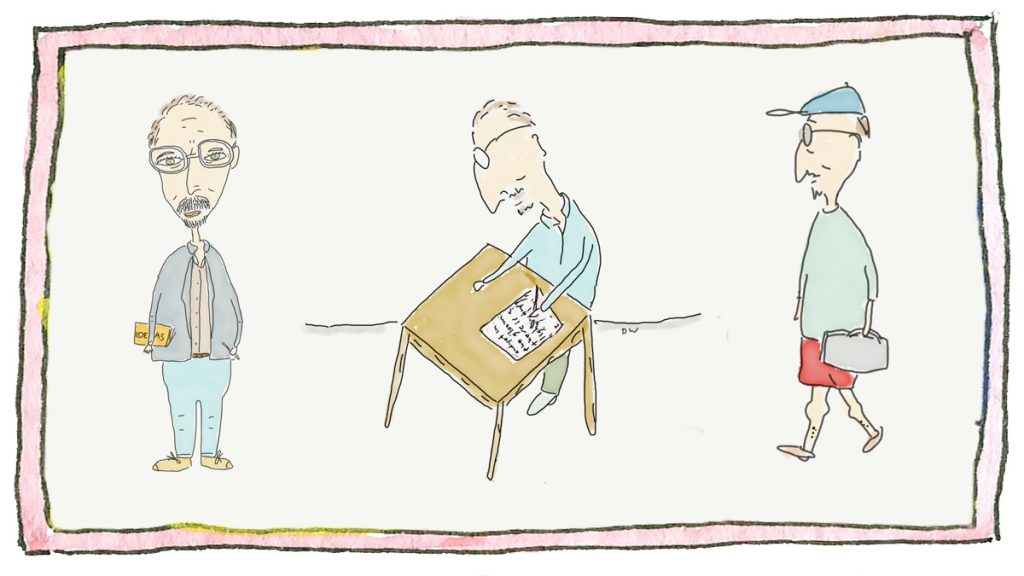

In an earlier incarnation of my life, in a prior marriage, neither of us had traditional full-time jobs. We were not poor but sort of treading water. We had two kids who were about 8 and 10. They would come downstairs in the morning on the way to school and be really grumpy. So I started drawing these cartoons to put by their cereal bowls that I hoped would cheer them up a little bit. One thing led to another, and my then-wife and I decided maybe we could put these drawings on refrigerator magnets, sell them and make a living doing that. Sure enough, that’s what happened. We made enough to keep all of us in cabbage for a while and neither of us had to get a real job, which was a big plus.

My work has never transcended the napkin doodle, and it always surprises me when people like my drawings. But we sold thousands of them. It was a great business for a while.

Why do you go by Daniel instead of Dan?

Great question. My father’s name was Dan. People call me Danny or Daniel. A person named Dan is older than I am, wearing a pair of wingtip shoes and cuff links, and with a much better retirement account than I have. I was Danny all my life until I went to college, and I thought, I’m going to get fancy and call myself Daniel. And that’s what I did. I’ve been Daniel for a long time. I’ve played with the idea of changing it back to Danny, though, just to keep things fresh.

Interview by Scott Jared, The Well