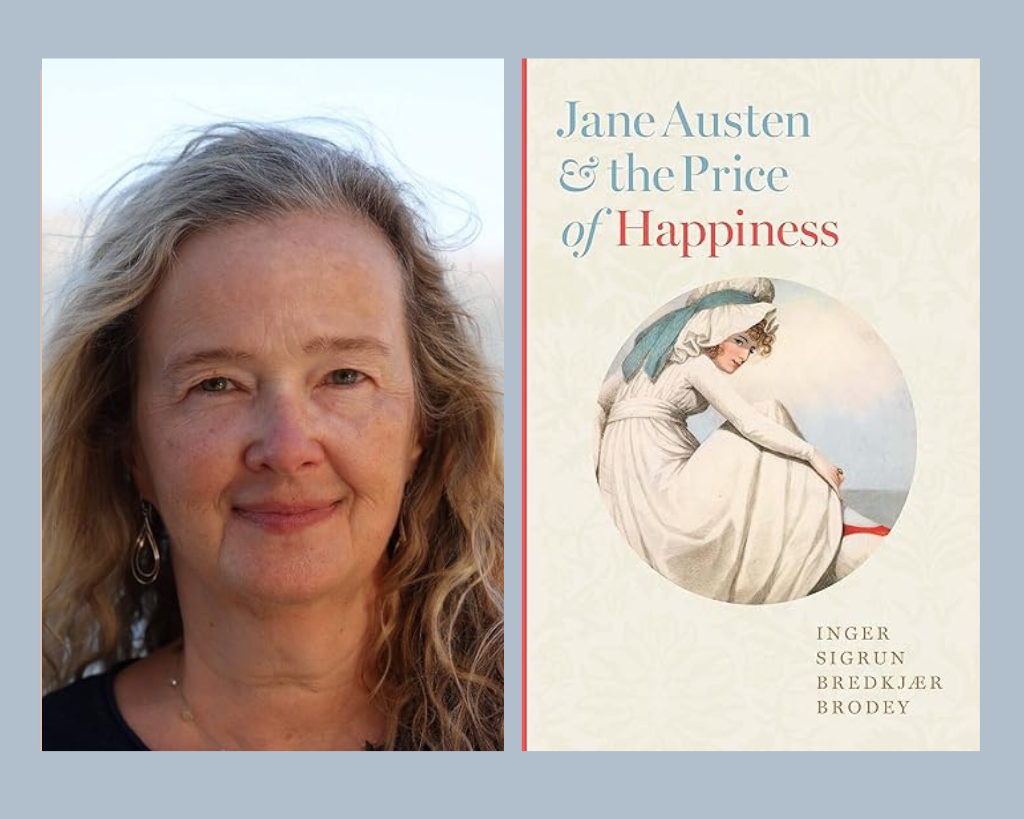

Bookmark This is a feature that highlights new books by College of Arts and Sciences faculty and alumni, published each month. The June featured book is Jane Austen and the Price of Happiness (John Hopkins University Press) by Inger Sigrun Bredkjaer Brodey.

Bookmark This is a feature that highlights new books by College of Arts and Sciences faculty and alumni, published each month. The June featured book is Jane Austen and the Price of Happiness (John Hopkins University Press) by Inger Sigrun Bredkjaer Brodey.

Q: Can you give us a brief synopsis of your book?

Q: Can you give us a brief synopsis of your book?

A: Lots of critics and readers have noticed the strangeness of Jane Austen’s endings. In the concluding chapters of most of her novels, she suddenly starts summarizing instead of providing dialogue, inserting herself as the author commenting on the book, and using many other techniques to heighten the readers’ awareness that we are reading fiction. This occurs at the moment where all true romantics would like to forget they are reading fiction and instead indulge in a dreamy fairy-tale ending. By going through each of her novels and including evidence from some of what Austen herself read, I establish her hidden purposes as a writer and teacher. Fierce independence, conviction in the potential of the novel as a genre and deeply humanistic ideals led her to develop a style of ending all her own. She wrote in a culture that set a monetary value on success in marriage and equated matrimony with happiness, yet Austen actively challenges these ideas in her endings. The book also includes a selection of adaptations of Austen’s endings in both fiction and film, thinking about which ones are able to capture the spirit of her endings.

Q: How does this fit in with your research interests and passions?

A: Austen has been a major part of my life since I first read her as a teenager in Colorado. Since college, I’ve been deeply involved in Jane Austen societies around the world, traveling to do research and give lectures. I’ve written dozens of articles on Austen; this is my first book exclusively on her. I’m also passionate about the public humanities and have built four non-profit organizations around Jane Austen — an annual in-person symposium in June called the Jane Austen Summer Program (www.janeaustensummer.org), a middle and high school teacher training program for teaching earlier works of fiction to students (www.jaspplus.org), an online Zoom interview series called Jane Austen & Co. (www.janeaustenandco.org), and a new interactive website/ portal called Jane Austen’s Desk (coming soon at www.janeaustensdesk.org). Accordingly, I’ve also written this book on Austen for a wide readership. I really love the town-and-gown communities.

Q: What was the original idea that made you think: “There’s a book here?”

A: Well, I first noticed how odd Austen’s endings were as a teenager, reading her for the first time. My older brother Hans Bjarne discovered her in college and introduced me to the novels. I remember getting to the ending of Mansfield Park, storming into his room, and demanding what Austen was up to. Mansfield Park’s ending is extremely short and dismissive; it’s particularly noticeable coming, as it does, after the enormous detail of the rest of the novel. I was angry at Austen for this. Over the past couple of decades, as Austen became a Hollywood megastar, the disjunction between the romanticized view of Austen and the fact of her oddly rushed and abbreviated endings became even more striking to me. I set out to see if I could understand exactly why she was doing this.

Q: What surprised you when researching/writing this book?

A: First of all, I was surprised to find that no one else had tackled this well-known problem in a book-length manuscript before. So much has been written about Austen that it is rare to find this kind of opening. Secondly, I expected to find that one or two of Austen’s novels would be exceptions to the rule, but I was wrong: Austen playfully distances readers from her happy endings in all her novels. I also discovered some surprising details. For example, Austen plays with extensive plot symmetry between the two volumes of Northanger Abbey. By doing that, she literally makes the happy ending stand out as an “extra chapter”— unnecessary to the plot. That makes her romantic happy ending a gift rather than an expectation.

Q: Where’s your go-to writing spot, and how do you deal with writer’s block?

A: I wrote the majority of this book in Cambridge, U.K., on a sabbatical research trip. I enjoy writing in coffee shops and libraries, rather than in isolation. I find the background noise helps. Otherwise I tend to feel like the world is passing me by while I write. My youngest child, Henry, is nearing the end of high school, and this has been a major help to my writer’s block as well. I found it difficult to complete book projects while my four children were young, especially alongside my many other responsibilities. Now I’m entering a new phase. I anticipate more Austen-related books in the near future.

Brodey is a professor of English and comparative literature, the co-founder and director of the Jane Austen Summer Program and Jane Austen & Co., and the principal investigator of Jane Austen’s Desk. Learn more about Brodey. Read a story about Jane Austen’s Desk.

Publisher’s Weekly writes: “Brodey’s interpretations of Austen’s writings are subtle and penetrating, and discussions of popular Austen film adaptations shed light on how Hollywood tramples over the novels’ ambivalence. Austenites will want to take a look.”

Join Brodey at a Flyleaf Books discussion and a book signing on June 11.

Nominate a book we should feature by emailing college-news@unc.edu. Looking for more faculty and alumni books to add to your reading list? Check out our spring ’24 College magazine books list.