Visiting professor Von Diaz shares how for many of us in isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, food is perhaps more meaningful than it ever has been.

Food writer and radio producer Von Diaz is teaching “Feeding Diaspora: Telling Global Food Stories” in the department of American studies in the College of Arts & Sciences this semester. The course is designed to train students on food storytelling through audio production.

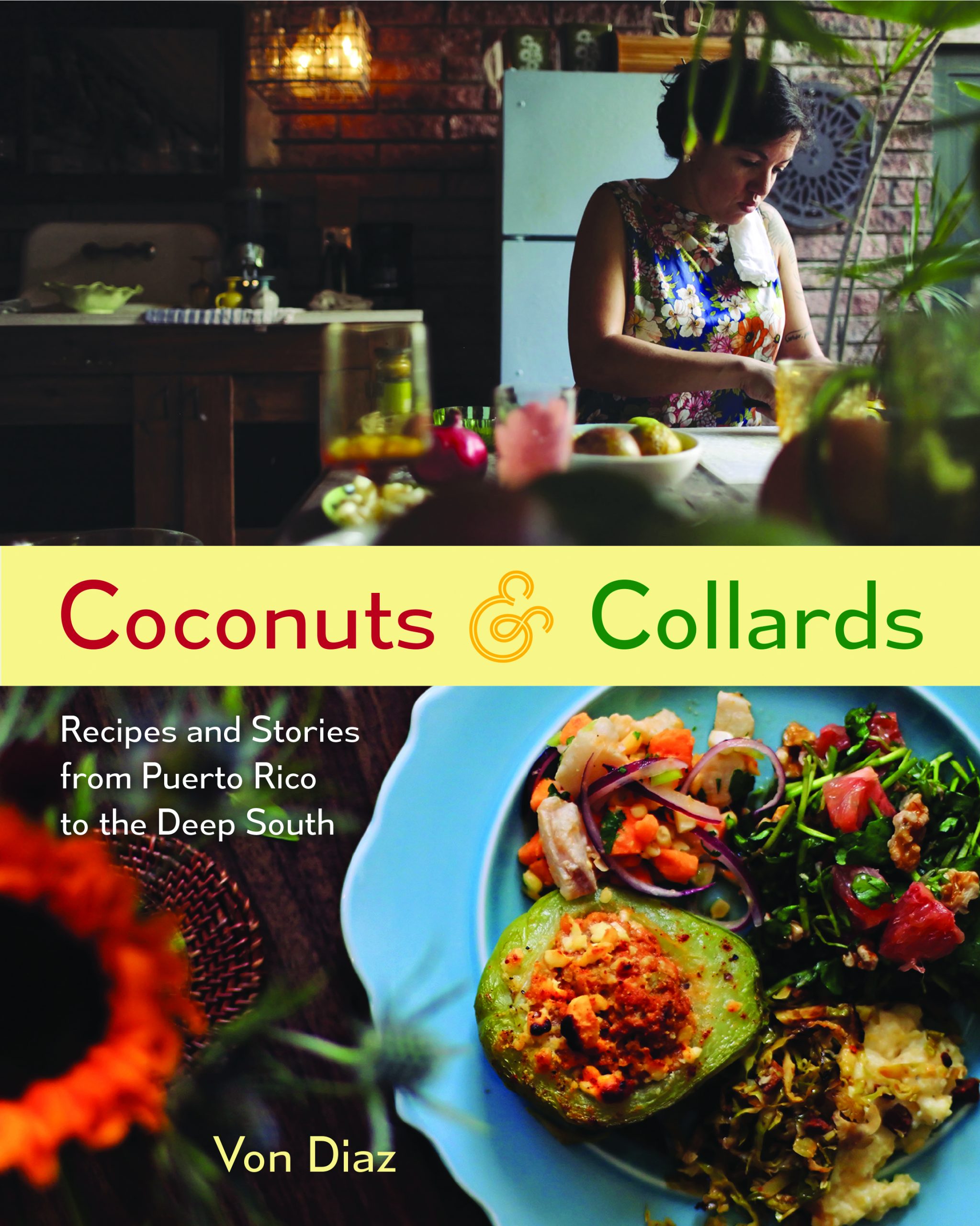

Diaz was born in Puerto Rico and raised in Atlanta, Georgia. She has produced content for StoryCorps and NPR, managed a Puerto Rican and Latino museum in New York City and worked on an original documentary film series and podcast at Google. Her cookbook Coconuts and Collards: Recipes and Stories from Puerto Rico to the Deep South has been featured in The New York Times, NPR, and The Splendid Table.

We recently chatted with Diaz about her American studies course, how she is adapting to remote instruction and her thoughts on food amidst the COVID-19 outbreak.

Q: You are the Lehman Brady Visiting Professor at both Duke and UNC this semester. What’s it been like to teach both UNC and Duke students (rivals on the basketball court!), and why is this collaboration important?

A: I’m truly honored to be among the Lehman Brady scholars and have enjoyed being on both campuses this spring. I’m new to the state, and am not a sports fan, so the rivalry is lost on me. But I can tell you that all my students are brilliant and engaged and seem to be getting a lot out of the interdisciplinary curriculum and documentary focus that the Lehman Brady professorship provides.

Q: With the switch to virtual classrooms, how are you adapting this course?

A: This was a huge challenge. Audio storytelling typically requires in-person interviews. That’s how you get high-quality sound recordings, which are essential for great podcasts and radio stories. That aspect of the course had to change, but my students had already done some remarkable work this semester, and I wanted to be sure they could still learn how to be skilled audio storytellers.

So, I invited my students to either continue with existing projects (recording phone or online interviews) or create an audio diary of their experience navigating COVID-19. That way students could make their own decisions about what they had the capacity to do, both practically and emotionally. It felt important to not make assumptions, but instead give them options that would be creatively stimulating and achievable.

We’re also being creative with the digital platform. Each week one student is responsible for presenting and leading a discussion with the entire class, which works well digitally. And we’ve also used Zoom “breakout rooms” that enable students to meet in small groups during the class period. While I miss being with them in person, it’s a true pleasure to see their faces every week.

Q: With the current global pandemic, especially with the production and distribution of food, do you think the way society views food culture will change?

A: Society must view food differently moving forward. The current crisis has exposed how fragile global food systems are. It has exposed, yet again, that the most vulnerable among us—people of color, folks living with income or food insecurity, women and children, folks with disabilities—will be disproportionately impacted. It has exposed that many of our staple food crops are harvested by immigrants, many of whom travel annually from their home countries to keep strawberries and watermelons in our grocery stores. We now know that the restaurants we love and consider part of the fabric of our communities cannot operate if their workers are not protected, and if they can’t get food to cook. In Puerto Rico, where I was born, 85 percent of food is imported. I worry about how those on the island will get enough to eat if supply chains are further disrupted. A global food system requires an equitable global response to crisis, otherwise the system that produces something we all need to live will collapse. This has never been as plain to me as it is in this moment.

Q: Food and enjoying meals is all centered around sharing and a table. How has the pandemic affected our ability to do this? Do you think people are finding new ways to share their love of food?

A: The divide between those with and without resources has been laid bare by this crisis in so many ways. Some are at home complaining about failed sourdough starters (true story) while many are out of work and without enough money to buy groceries. Millions of children across the nation rely on school lunch or breakfast assistance in order to eat, and are likely not getting the nutrients they need. But I’ve also heard hopeful stories. Local farms across the nation are organizing and delivering healthy vegetables at affordable prices to help keep farms afloat. Restaurants are shifting menus and adjusting store hours, delivery and pick-up options to keep folks fed. My neighbors, who I hadn’t met before the crisis, left fresh baked bread on my porch.

For many of us in isolation, food is perhaps more meaningful than it’s ever been. In homes across the country, families are cooking and eating together, and learning to make due with limited ingredients. Cooking is a practice, and making a meal is one of the best gifts you can give to your loved ones. Despite it all, it makes me happy to see so many people finding new comfort in cooking and eating it during this difficult moment.

Want to try cooking something new while at home? Diaz shares these recipes from her book Coconuts and Collards:

Want to try cooking something new while at home? Diaz shares these recipes from her book Coconuts and Collards:

Interview by Lauren Mobley ‘22