UNC-Chapel Hill folklorist Glenn Hinson and playwright Jacqueline Lawton are working with community members to examine difficult topics in Warren County’s history and to help forge a new future.

“Plummer was so much light and energy, and then he was just gone. White folks my Momma had known all her life had killed her boy, my brother, over what amounted to nothing, and Momma was so stricken. Daddy decided they had to leave Warren County.” — written and performed by Tampathia Evans for a monologue in the voice of Martha Bullock Shearin. Shearin was the sister of Plummer Bullock; he was lynched in 1921 in Warren County.

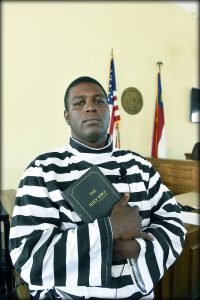

Five local women wrote first-person monologues this summer to illuminate the story of a 1921 court trial of a group of Black men who became known as the “Norlina 16.” Threatened with violence by members of a white mob, the men had armed themselves to protect their families.

In all, 18 Black men were arrested and unfairly unaccused, but two never made it to trial: Cousins Plummer Bullock and Alfred Williams were dragged from jail less than 24 hours after being arrested and lynched.

Warren County resident and UNC alumna Tampathia Evans (B.A. African American studies ’00, M.A. English and comparative literature ’02) is an assistant professor of English at Louisburg College and was one of the monologue writers. She reconnected with Glenn Hinson — a Carolina professor she had as an undergraduate — for this work. She was asked by Warren County community activist Jereann Johnson and Hinson to take on the role of Martha Bullock Shearin, the sister of Plummer Bullock.

Growing up, Evans had never heard the story of the 1921 court trial. She had heard stories about Bullock’s brother, Matthew, who was also involved in the altercation, and escaped to Canada where he successfully fought extradition.

To mark the 101st anniversary of that trial, Hinson, an associate professor of anthropology and American studies, and Jacqueline Lawton, an associate professor of dramatic art, worked with local playwright Thomas Park to weave the monologues into the original script of the trial re-enactment; the first performance of the play was held last year.

“Attending the trial re-enactment last year was really illuminating; it was a teachable moment,” Evans said. “It was so moving to me, and I jumped at the chance to be involved this year.”

Panel discussions help reclaim history

Five panel discussions with the theme “Liberating Futures: Erasures, Reckonings and Transformations,” were held at the Warren County Memorial Library on successive Saturdays leading up to the trial re-enactment on June 25. Blair L.M. Kelley, who will direct UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South in 2023, led one of those panels.

The sessions were sponsored by the 1921 Project, the Warren County African American Historical Collective, the Warren County branch of the NAACP, UNC’s Humanities for the Public Good initiative, and the Descendants Project, a long-term UNC initiative led by Hinson that has been collaborating with communities to uncover the legacy of lynchings in North Carolina. The Descendants Project secured funding for both the 2021 and 2022 re-enactments and the panel series. Hinson’s students’ research has informed the programming and provided the biographical material for the vignette writers. Hinson also spent time on the project through an Institute for the Arts and Humanities Race, Memory and Reckoning Initiative Fellowship.

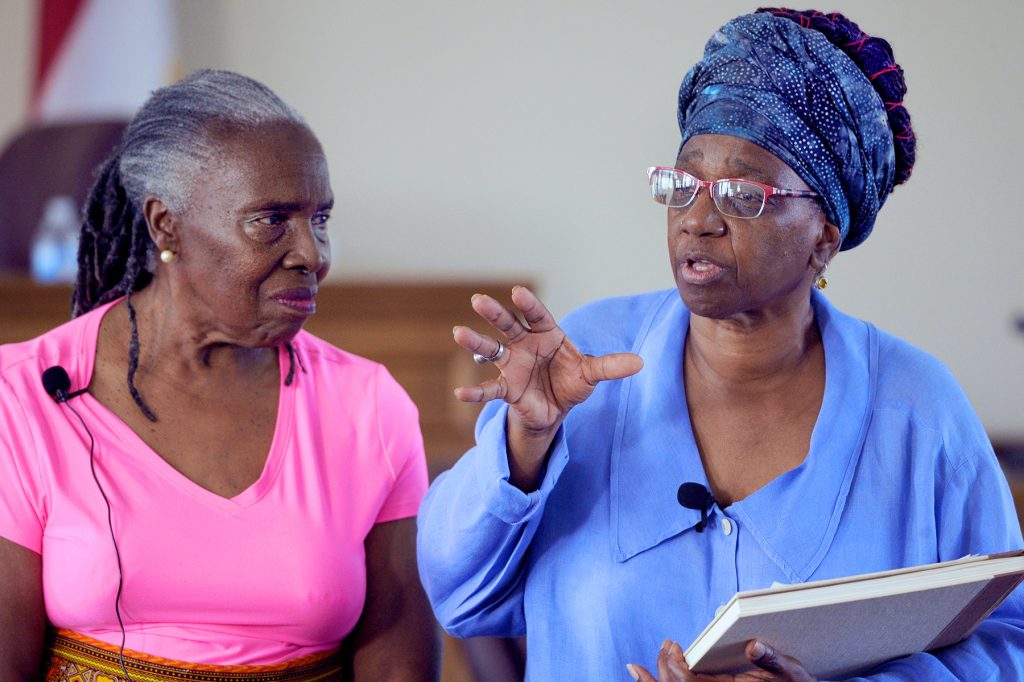

Panel topics, each addressing a dimension of regional history, covered “Legacies of Enslavement,” “Histories and Futures of Education,” “Black Progressive Thought,” “Ties to the Land: Sharecropping, Black Land Ownership and Black Land Loss,” and “Descendants’ Stories,” the last of which brought together descendants of victims of racial terror murders in Warren County. A diverse mix of community members, historians, educators and humanities scholars packed the library for lively conversations and questions.

“In reflecting on how those acts of terror shaped how we are today, it’s about building a better future; that’s how we came up with the overall title of ‘Liberating Futures,’” Johnson said. “History can bring communities together, offering a path for moving forward.”

At the heart of the discussions were the questions: “What counts as history? Who controls its telling? Why is history important to the present day?”

Evans, who was a moderator for one of the panels, said it’s important to share these stories with younger generations.

“These discussions illustrated the long history of social activism within this community which can be traced back to the Norlina 16, through the Civil Rights Movement, the development of Soul City in the 1970s, the establishment of one of the earliest Black radio stations in North Carolina, the birth of environmental justice and on into the 21st century in Warren County,” Evans said. “These events serve as powerful examples of how to make change.”

The panel discussions were recorded, and copies will be made available in the local library and the Warren Community Center and at Wilson Library in Chapel Hill.

New monologues add emotional depth to the story

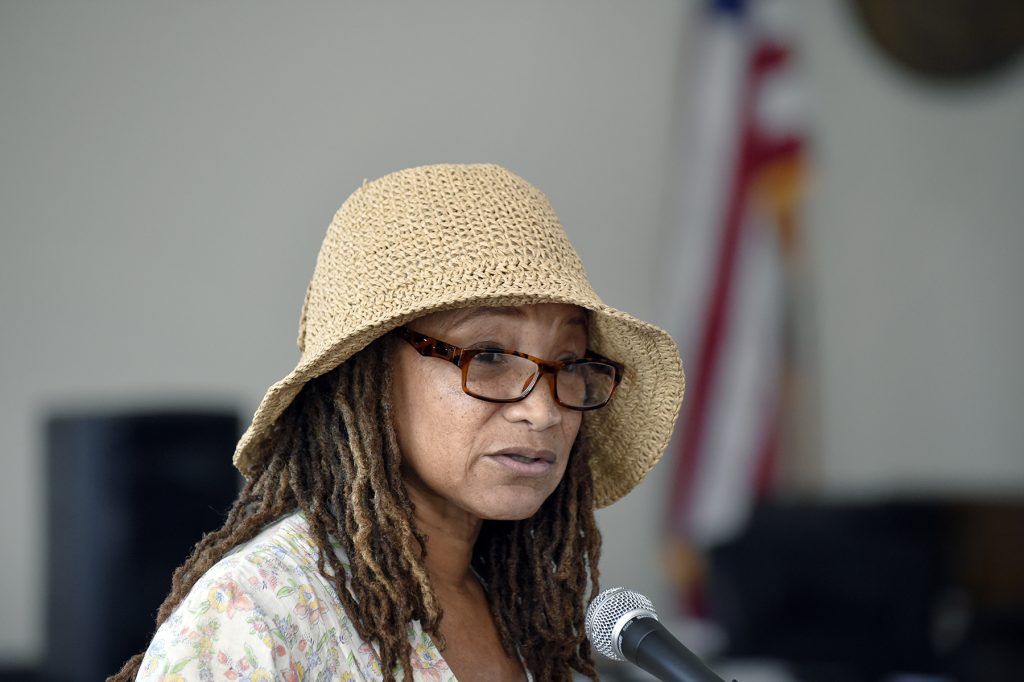

Lawton held weekly Zoom workshops with Hinson and the five monologue writers as they crafted their vignettes and sought to capture the emotional experiences of their characters.

“We know the testimony that was given the day of the trial (through legal documents), but there were people who were not allowed to tell their stories or go into the courtroom — people who were impacted directly because their loved ones were involved,” Lawton said. “What were they feeling that day? What did they feel in the aftermath of the trial? Do they want to say something to the people they lost? From there, we started to build out narratives.”

Evans decided to place her character, Martha, outside the courtroom door.

“She’s standing there on the morning of the trial with her infant son,” she said. “All of these events — the trial, the lynching, the loss of her brother, her own marriage and the birth of her first child — all of that happened within a year.”

Johnson resumed her role as a narrator in the play this year, but also became a monologue writer. Her character was Salome Coleman, who would later become the wife of Jerome Hunter, who was sentenced to eight years in prison. The two married after his release and moved to New York.

“I think all of us brought our own sensibility and sensitivity to writing our stories,” Johnson said.

Lawton, whose own work often focuses on social justice, said she was humbled and honored to guide the women on this writing journey.

“It was really beautiful to hear them as storytellers speak about the legacy of their community, a heartbreaking legacy, but also the resilience of their community and what they hope to never have repeated again. This was a history that was not supposed to be remembered, but we’re making sure it is known and told.”

Hinson said that adding the new vignettes to the play, “Seeking Justice,” brought emotional power to the story. This year’s production was also videotaped.

“These first-person narratives rip at your spirit,” he said. “One of the writers was the first African American woman jailer in North Carolina who had worked in the Warren County jail for 17 years and had never heard this story. She wrote from the perspective of the Black male jailer at the 1921 trial who was not allowed to testify. When one of the community members read her monologue, there were moments when he started crying. He was not acting; he was just trying to get through it. There were a lot of moments like that.”

Johnson said the opportunity to continue this work in concert with UNC offers a critical model for how universities and communities can work together.

“The resources that the University has brought to us has made a lasting impact on this community,” she said. “We have a long way to go, but this experience has taught us a lot about courage and persistence and the value of research and of telling our own stories.”

Hinson added: “The reverberations from the panels and the play are still being felt. I think we can serve as a facilitator and a spark and to help do the work and make connections, but our role is not to direct. It’s to invite communities to decide how this material should be addressed and presented. This is about collaboration, about scholarship in service of the community’s creativity.”

By Kim Spurr, College of Arts and Sciences

More photos from the re-enactment (all by Donn Young). Click on each photo for a larger size: