There have been more than 1,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in poultry and other meat processing plants in North Carolina, and over 10,000 cases across the United States. The industry is the subject of UNC-Chapel Hill anthropologist Angela Stuesse’s scholarly work, but it’s also personal. Celso Mendoza, a friend, longtime research collaborator and worker in a Mississippi poultry plant, died May 2 from the coronavirus. He was 59.

Angela Stuesse first met Celso Mendoza, an immigrant worker at a chicken processing plant in Forest, Mississippi, in 2002 when she was a young graduate student.

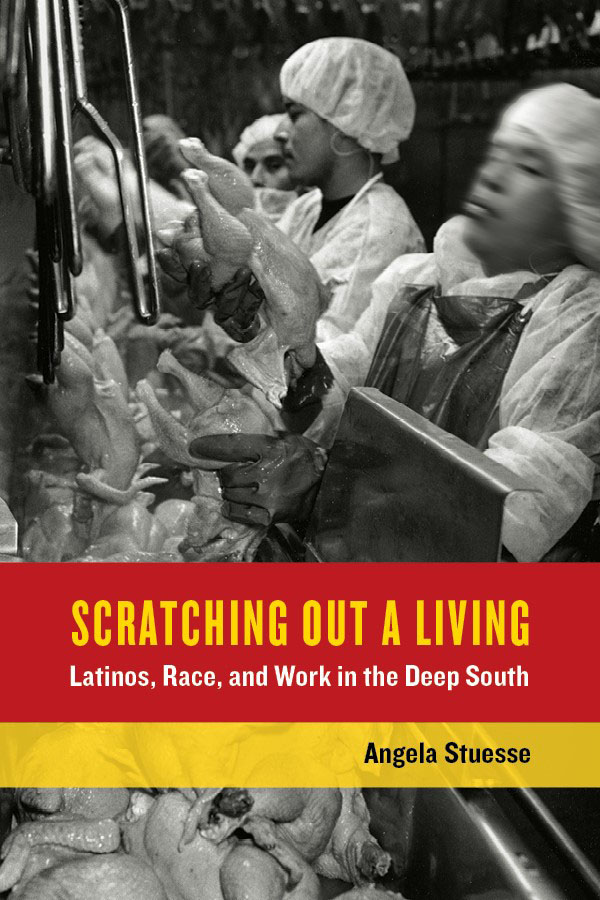

He had migrated from Veracruz, Mexico, to work in the chicken plant for $6 an hour. As Stuesse sought to understand how her ethnographic research into the poultry industry might benefit real people’s lives, Mendoza opened his doors to her. She documented the lives of Mendoza and many of his coworkers and families through her time at a local worker’s center in her 2016 book Scratching out a Living: Latinos, Race and Work in the Deep South (University of California Press).

The last time she visited Mendoza was to hand deliver an inscribed copy of the book.

His son, Daniel, called to tell her of his father’s passing on May 2 from COVID-19. Daniel found a copy of the book and a photo of Stuesse and Mendoza in his father’s apartment.

“Celso is one of many people that I am indebted to who taught me so much about a subject in which I’m now able to claim some expertise,” said Stuesse, an associate professor of anthropology and global studies in UNC’s College of Arts & Sciences. “I want to draw attention to the way our food is produced and to the people who are suffering for us to be able to buy cheap chicken.”

Stuesse wrote an op-ed about her friend that was published May 12 in USA TODAY.

“If we value all lives, we must take action to protect all lives, including those of the mostly black and brown hardworking people who keep America’s food chain running,” she wrote.

Vulnerable workers, unsafe conditions

Increasingly more and more these days, Stuesse is fielding national media calls alongside pursuing her research.

In early May, she participated in a virtual press conference organized by the N.C. Justice Center, the state AFL-CIO and the Western North Carolina Workers’ Center. Advocates urged state leaders to wait to open up the state until they can protect those who have been working throughout the pandemic. They asked that they enact rules requiring meatpacking and other essential employers to follow guidance on workplace safety and protect their employees from COVID-19.

When President Donald Trump invoked the Defense Production Act ensuring that meat processing plants stay open, this created more problems for already vulnerable workers, Stuesse said.

“If there’s one thing I have learned it’s that the poultry and meatpacking industry will do everything they can to keep running the lines,” she said. “The processing lines operate at incredibly high speeds. Workers are tightly packed together, elbow to elbow, making the same repetitive movements 60,000 times a day. It’s loud, so if you want to communicate, you have to be right next to your supervisor or coworker.”

Those physical conditions are compounded by the fact that many of the workers are already in precarious economic positions, she said. Very few have health insurance or paid sick leave. Many are undocumented, without a safety net. Many don’t qualify for unemployment or stimulus money.

“People are in a Catch 22 where they know it’s dangerous to go to work, but they have to go because they desperately need the money. If they don’t go, they risk losing their jobs or their homes,” she said.

Study abroad opened her eyes

Stuesse’s research more broadly explores the recent influx of Latin American migrants in the U.S. South and how it is impacting regional identities, racial hierarchies, industrial relations and labor organizing.

Although she did her master’s and doctoral work at the University of Texas at Austin, it was study abroad during her undergraduate career at the University of Florida that began to open her eyes to a different way of seeing the world.

She studied abroad in Spain, Mexico and Venezuela, but living with a Mexican family as an exchange student had the greatest impact.

“In some ways it was isolating and lonely but in other ways, I grew tremendously,” she said. “The family I lived with employed a young indigenous woman as a domestic worker to do their cooking and cleaning. We were close in age, and the time I spent talking with her over several months really opened my eyes. That experience helped me realize how much privilege I had as a U.S. citizen and as a white, educated woman and sparked my interest in inequality and social difference and labor exploitation.”

At Carolina, Stuesse is among a number of collaborators who formed UndocuCarolina, with help from a Humanities for the Public Good Critical Issues Award. The initiative strives to create dialogue and make the campus a more welcome space for people living with the effects of undocumentation. They’ve hosted community conversation events, workshops, movie screenings and ally trainings.

“The ally trainings address: What does it mean to be undocumented, and what are the issues people face?” said Stuesse. UndocuCarolina has offered 10 ally trainings since launching in fall 2018. Now that organizers have built a volunteer network of 25 trainers (including volunteers from campus, the community and private immigration lawyers), they are hoping to offer even more ally trainings next year.

#FreeDany: Dreaming and Detention in Dixie

Stuesse has spent the past year on a fellowship at the National Humanities Center working on a co-authored book project with Dany Vargas of Jackson, Mississippi.

In 2017, as immigration raids increased across the country, Dany’s father and brother were seized from their home as they left for work one morning. Because she had protected status from deportation under the policy DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, Dany was initially left alone. But after she spoke out a press conference about her family and her fears of deportation, Dany was arrested by Immigrants and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials and put in a detention center. The 22-year-old had lived in the United States since she was 7.

Stuesse and other citizens, advocates and undocumented youth leaders mounted a national campaign called #FreeDany, and 10 days later, Dany was freed.

Dany graduated in May from Trinity Washington University in Washington, D.C., and wants to go to graduate school in public health. #FreeDany: Dreaming and Detention in Dixie will show through Dany’s perspective how the lives of undocumented youth in the 21st century United States have been indelibly shaped by the country’s discourses and policies on immigration.

“It’s exciting from a scholarly standpoint because I’ve always been interested in collaborative research that contributes to people’s efforts to improve own their lives, but there are not a lot of examples of what that looks like in the writing process. So this book project Dany and I have undertaken is sort of an experiment,” Stuesse said.

Stuesse, who came to Carolina in 2016, said she has found a supportive environment at Carolina for her research. In her online bio, she calls herself an “activist researcher.”

“UNC clearly positions itself as a university for the public, interested in solving social problems that our state and nation face,” she said. “So Carolina has been a great fit for me. I’ve found it to be a place where I can pursue scholarship and teaching that really matter.”

By Kim Spurr, College of Arts & Sciences