New common framework developed by a team of top scientists will help research into climate-threatened ocean reefs around the world.

An international consortium of scientists that includes UNC-Chapel Hill’s Karl Castillo has created the first-ever common framework for comparing research findings on coral bleaching.

“Growing up in Punta Gorda Town, in southern Belize, and visiting the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef regularly, gave me a bird’s-eye view of the transition from reefs that experienced no bleaching to reefs that now bleach almost every year,” said Castillo, associate professor in the department of marine sciences and the Environment, Ecology and Energy Program. “I am thrilled to be a part of the team that has developed a common framework to tackle a crisis of direct relevance to my life and the lives of people worldwide.”

The international team developed a series of guidelines in a paper published in the journal Ecological Applications.

“Coral bleaching is a major crisis and we have to find a way to move the science forward faster,” said Andréa Grottoli, a professor of earth sciences at The Ohio State University and lead author of the paper.

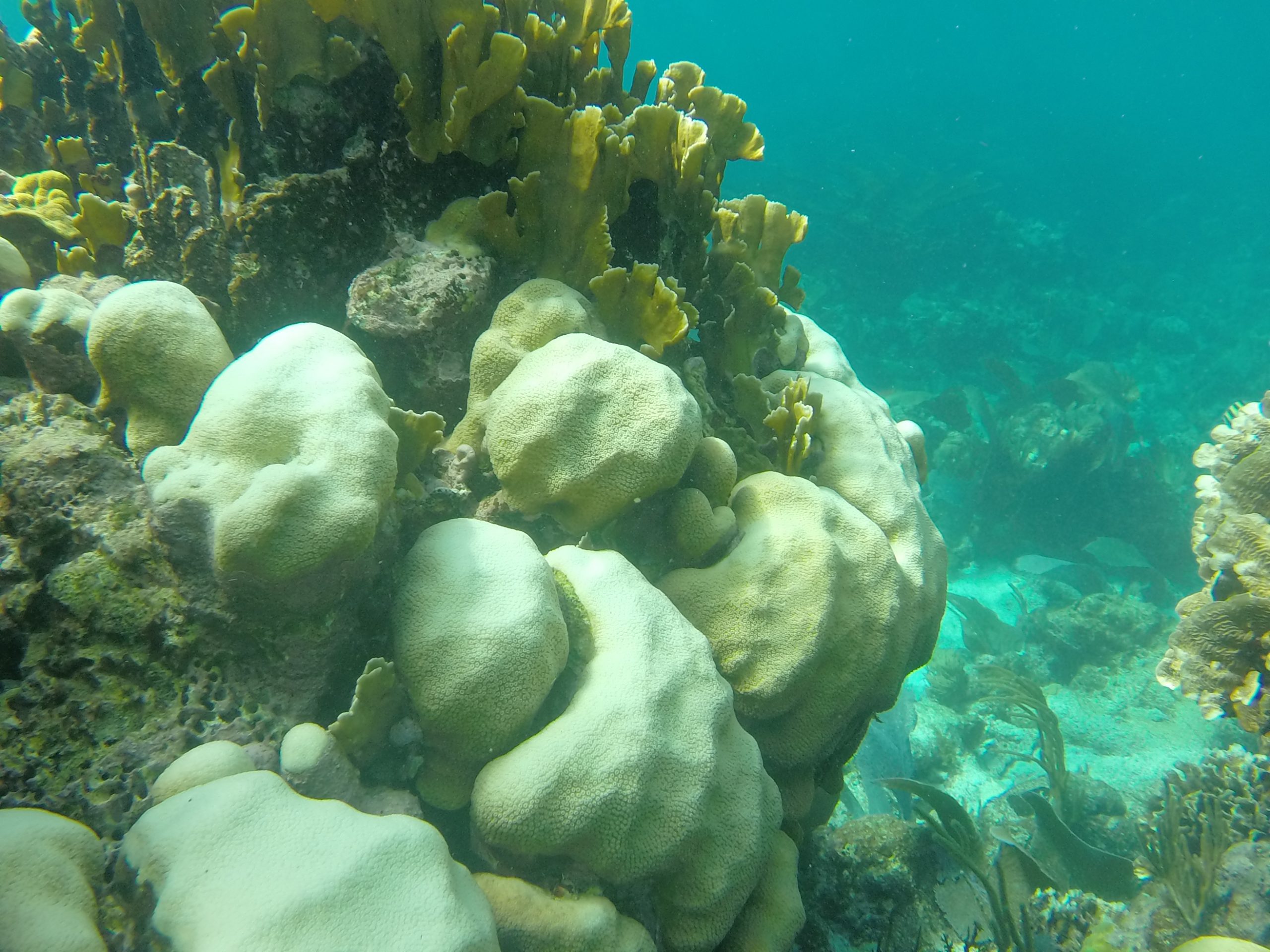

Coral bleaching is a significant problem for the world’s ocean ecosystems: When corals become bleached, they lose the algae that live inside them, turning them white. Corals can survive bleaching but being bleached puts corals at higher risk for disease and death. And that can be catastrophic: Coral protects coastlines from erosion, offers a boost to tourism in coastal regions, and is an essential habitat to more than 25% of the world’s marine species.

Bleaching events have been happening with greater frequency and in greater numbers as the world’s atmosphere — and oceans — have warmed because of climate change.

The common framework, highlighted in the paper, covers a broad range of variables that scientists generally monitor in their experiments, including temperature, water flow, light and others. It does not dictate what levels of each should be present during an experiment into the causes of coral bleaching; rather, it offers guidance that facilitates comparing results across experiments. This capacity to compare across studies is critical because it will allow scientists to consolidate the knowledge gained and take a more unified approach to combat coral bleaching.

“Reefs are in crisis,” Grottoli said. “And as scientists, we have a responsibility to do our jobs as quickly, cost-effectively, professionally and as well as we can. The proposed common framework is one mechanism for enhancing that.”

The consortium leading the effort is the Coral Bleaching Research Coordination Network, an international group of coral researchers. Twenty-seven scientists from the network, representing 21 institutions around the world, worked together as part of a workshop at The Ohio State to develop the common framework.

“This new network will also allow the formation and collaboration of interdisciplinary teams to work on the crisis of coral bleaching,” Castillo said. “We received input in real-time via several online platforms from other scientists at our first workshop. This inclusive approach will help accelerate the acceptance of this common language and move important future research forward faster.”

That such a common framework hasn’t already been established is not surprising: The scientific field that seeks to understand the causes of and solutions for coral bleaching is relatively young. The first reported bleaching occurred in 1971 in Hawaii; the first wide-spread bleaching event was reported in Panama and was connected with the 1982-83 El Niño.

But experiments to understand coral bleaching didn’t really start in earnest until the 1990s — and a companion paper by many of the same authors found that two-thirds of the scientific papers about coral bleaching have been published in the last 10 years.

Researchers are still trying to understand why some coral species seem to be more vulnerable to bleaching than others, Grottoli said, and setting up experiments with consistency will help the science move forward more quickly and economically.

“Coral bleaching is the single largest global threat to coral reefs. Countering this problem will require a concerted worldwide effort employing information from myriad published experimental studies,” Castillo added. ”Adopting a common language will further enhance our understanding of coral bleaching as we strive to combat climate change-induced ocean warming.”

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation.