Bookmark This is a feature that highlights new books by College of Arts & Sciences faculty and alumni, published the first week of each month.

Bookmark This is a feature that highlights new books by College of Arts & Sciences faculty and alumni, published the first week of each month.

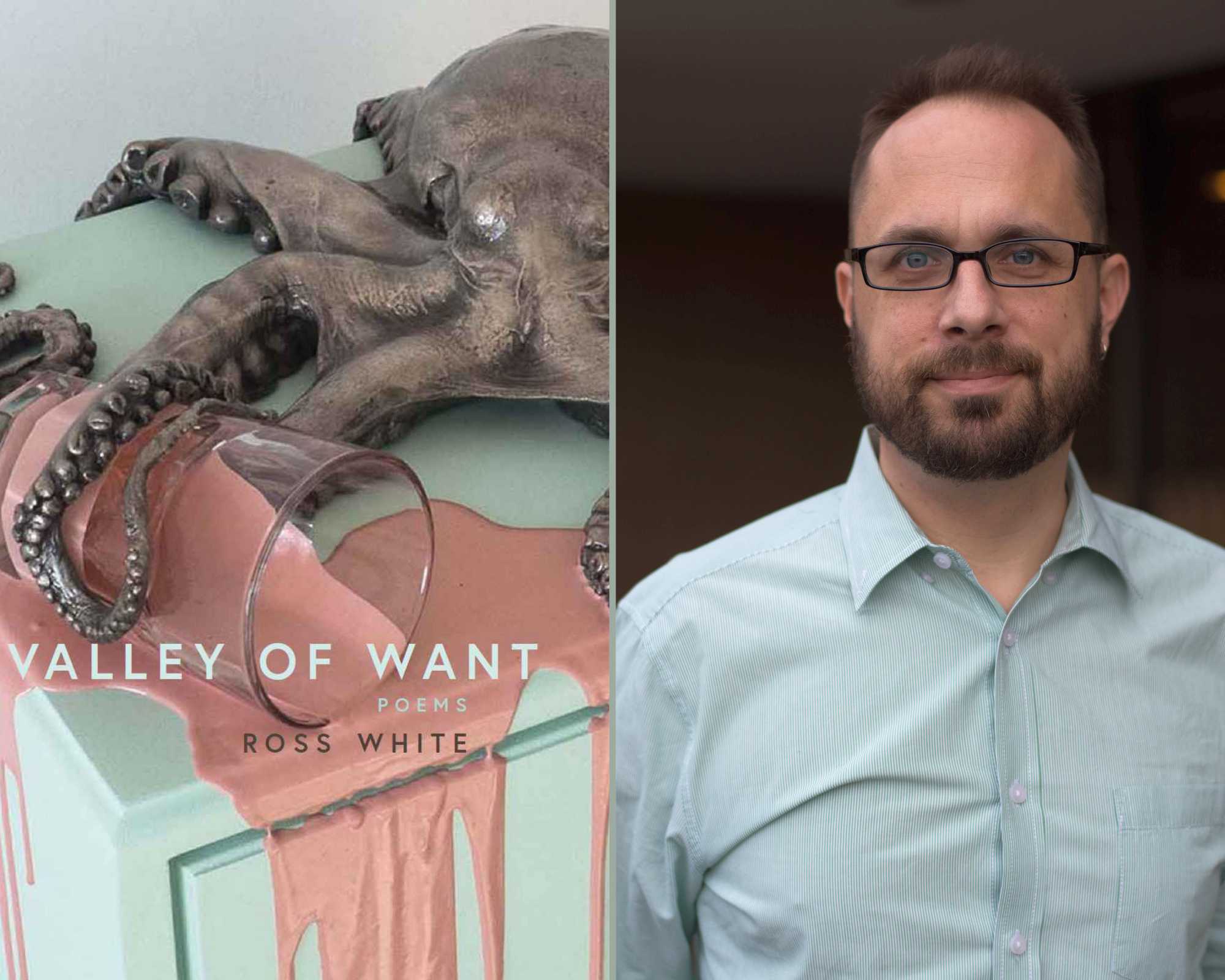

Featured book: Valley of Want (Unicorn Press, January 2022) by Ross White.

Featured book: Valley of Want (Unicorn Press, January 2022) by Ross White.

Q: Can you give us a brief synopsis of your book?

A: Valley of Want is about the difficulty of naming, or even describing, the thing you know to be true. These poems look at the performances we put on and the fictions we create in the hopes that those stories will tell us who we are.

Q: How does this fit in with your research interests and passions?

A: My first two books focused on periods of upheaval in the American experiment, and this one certainly picks up that thread. As Americans, we’ve had a harder time talking to each other since 2016 and a harder time agreeing on what reality is. We want an easy story that can explain that difficulty; we want someone we can hold responsible. So there are several poems that explore the idea that if you go looking for monsters, you’ll find them, even if you have to turn your neighbors and fellow citizens into monsters to do so. But this book also has a more personal upheaval at its heart: I got sick. I was diagnosed in late 2018 with a rare, progressive eye disease that bends my cornea, and my vision literally changes throughout the day as the shape of my eye changes. So I’ve had to go through the process of re-learning my body, and that’s also meant renegotiating the story I tell myself about who I am and how I interact with the world.

Q: What was the original idea that made you think: “There’s a book here?”

A: A number of these poems had already been written before I had a sense that they’d come together as a book, because poems tend to be the way I make sense of my world. And I had a lot of sense-making to do when I got sick. But the book came into focus after a poem called “Illness Narrative” (see below), which recognized that the world offers us so much splendor and astonishment, and we’re often too busy with our own tragic narratives to notice — and that was exactly what I had been doing. After that, I began tilting back toward wonder and gratitude.

Q: What surprised you when researching/writing this book?

A: Can I just say “everything” and leave it at that? One of the joys of poetry for me is that I almost never know where a poem is going to go when I sit down to write it. Heck, I hardly even have an idea to get going. I usually start with something directly in my line of sight and respond to that, and from that point on, it’s a consistent process of discovery. I’ll discover how I feel about that initial response, or I’ll discover that the thing I’m looking at is related to some memory or evokes a feeling that’s connected to something else that’s going on in the world. I’ve loved learning that my poems are often so much smarter than I am, and I’ll often come back to them later and think, “Did I really write that? It sounds way too smart to be me.” (Don’t get me wrong, I’ve also written plenty of drafts that I return to and think, “Wow, whoever wrote that was a grade-A dolt.”)

Q: Where’s your go-to writing spot, and how do you deal with writer’s block?

A: I do a lot of my best writing on my back deck in Durham. I’m a morning writer, and love to get out there with the dew and listen to what’s happening in the woods behind our house or see what the spiders have spun on between the eaves. I don’t know that I ever really feel like I have writer’s block because I don’t usually start with something I really want to say. I just try to treat each initial image or line of the poem like a gift — open it up and see what’s inside. I’m also surrounded by a far-flung, loving community of poets, and we play games with each other to keep from being stagnant. Matthew Olzmann or Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach will send me a list of titles and challenge me to write poems to fit, and I’ll do the same for them. Dilruba Ahmed and I meet on Skype every Friday, and we expect each other to show up with a new draft, so there’s some friendly pressure there. And I’ll often participate in The Grind, a monthlong challenge where you have to write a new draft each day and send it to a small group of fellow writers — the group isn’t there to comment, they’re just there to hold you accountable, and you’re doing the same for them. But when you read their wild poems hitting your inbox each day — some of which are brilliant and some of which are bananas — you find that you have a lot to be in conversation with.

White is teaching assistant professor of creative writing in the department of English and comparative literature. He is also the executive director of Bull City Press, a Durham-based literary press focusing on chapbooks of poetry, fiction and creative nonfiction.

White shares the poem “Illness Narrative” from his new book:

ILLNESS NARRATIVE

Because I am horrible,

I don’t care about your illness narrative.

I am sick myself. Of myself. & so magnolia

hurls its white blossoms toward spring,

& so the weevils stain the cotton

with their young. Take this new scarf,

this crude wooden figurine of a long-nosed troll.

My lungs are dark & stringy, contaminated

by the nearby, listless heart. & so fishermen

wrench pollock from the sea & walleye

from the river, & so pails fill with milk.

Tell me a story that doesn’t end

in senseless trauma. I don’t care

what you have to go through

to conjure it. & so the godwits

thrust their bills into the black shore,

& so the grackle’s black feathers

stain blue skies seeking a friendly branch.

It is easier to invent than to listen.

Through the window, I see the world

wondering how to stun us all

with its magnificence but everywhere

the wounded are walking & talking.

& so the anchors find the waiting seabed,

& so the moon rides up on its dark chariot.

Tell me that story, the one where night

lifts its lesser stars & strokes them

like pets, & the incensed sun lashes

its reflection to a hunk of rock

revolving around earth. & so

all shadows will be reminders, enough

sometimes to make me feel loved.